André 3000’s One Man Show

Text by Donovan X. Ramsey

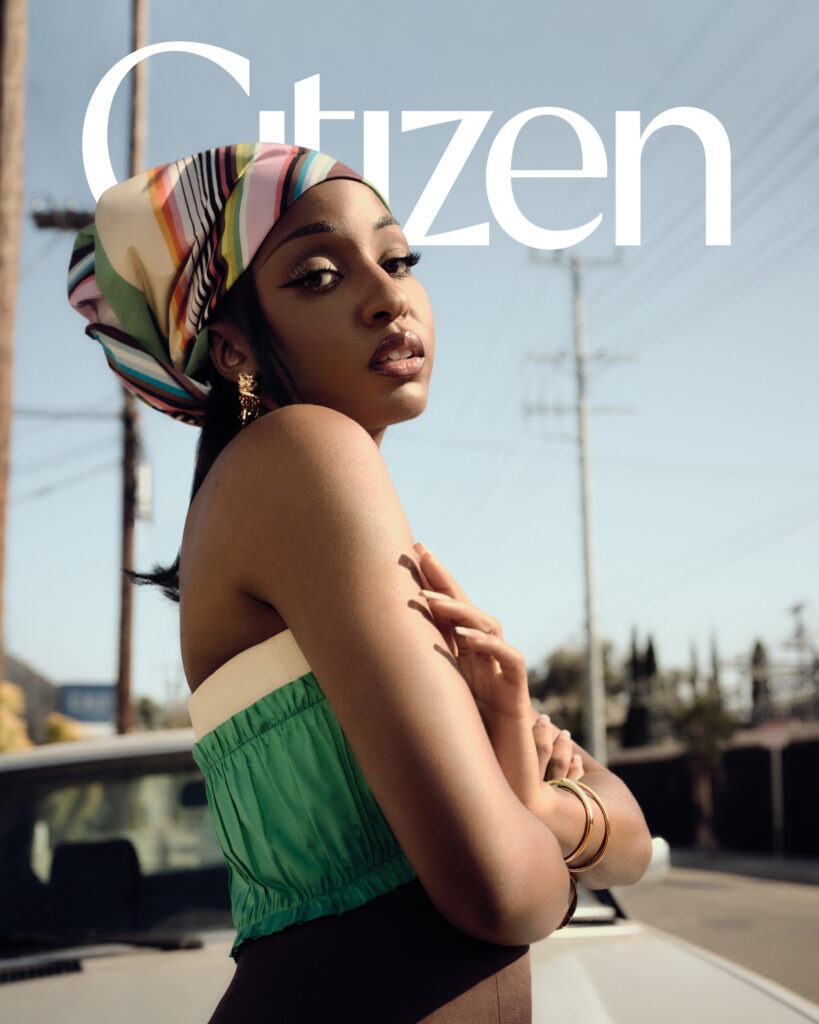

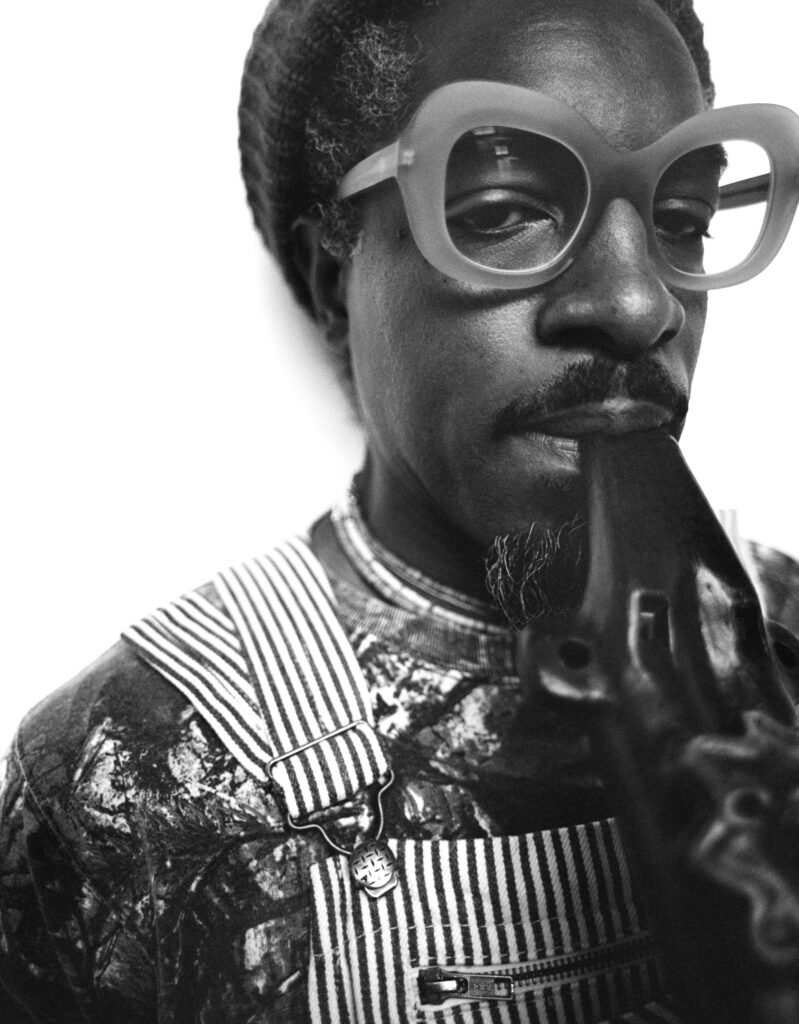

Photography by Bolade Banjo

Issue 003

André 3000 is back. With a solo album none of us could have anticipated. Over email, on Zoom, and then in a small sun-lit studio near his home, André talks with Donovan X. Ramsey about where he’s been, his unexpected artistic evolution, and only doing what “feels good.”

“Once it stops feeling good, why do it?”

The location is tucked away in South Los Angeles, nestled between a tire shop and a quaint family restaurant. I learned later that the unassuming structure was once a theater, constructed in the elegant Art Deco style of the 1940s. Without ornate adornments, it more closely resembles a spaceship that crash-landed in an urban landscape. The facade of the stone cube features sharp lines and bevels, with a solitary slender column that once held a neon sign, reaching skyward like an antenna.

Inside, a dozen or so people scurry around what’s been transformed into a spacious, white-walled studio. It is late fall, hot, and a door is propped open to let air in. The photographer and his team are busy checking lighting equipment and camera settings. Producers engage in hushed conversations while editors dart around, addressing last-minute questions and sharing information. Amidst the whirlwind of preparations, André 3000 sits serenely in a dimly lit dressing room.

I’m there, like everyone else, to observe him. I fail to spot him in the dressing room, at first. His back is to the door, but I get a glimpse of André in the large mirror that covers the wall in front of him. He says “hello” and waves the moment I recognize him. It’s the measured “hello” of someone who’s been recognizable for 30 years, just warm enough to make you feel seen while also saying, “One moment, please.” I leave him to it, a little stunned by my brief contact with the ATLien.

“Isn’t it the most awesome when life surprises us in a way that becomes greater than anything we could have imagined?”

Moments later, he emerges from the dressing room as ready as I’ve ever seen anyone. He’s wearing a pristine camo-print shirt beneath railroad-striped overalls, and not just any overalls but double-kneed ones with zippered bib pockets and a tailored fit with darts behind the knees. His goatee is neatly groomed, and his salt-and-pepper fro is tucked under a red beanie. Oversized mod glasses frame his face, and on his feet, he sports impeccably clean original Nike Air Tech Challenge IV sneakers.

He listens intently to the photographer’s instructions before taking his mark. With a camera trained on him, André moves with the careful intention of a mime or a silent film actor. Each movement is a symphony of subtlety, a dance of nuanced gestures. A raised eyebrow, a half-smile, and the subtlest tilt of the head convey an entire narrative. With every step, he glides, and the studio becomes his stage. It’s André 3000’s one-man show.

“I don’t know what the fuck I’m gonna be tomorrow. That’s fun and scary,” he admits. “My whole journey has been a trip, and I’m watching it just like y’all.”

Music-wise, Andrė has been relatively quiet for quite some time. He drops guest verses almost as proof of life and proof that he hasn’t lost “it”: his penchant for brevity, original flow, wordplay, and phrasing. His guest appearances also read like thread uniting seemingly disparate artists, effortlessly weaving between fellow Southern rappers like Killer Mike, Rick Ross, and Young Jeezy, and pop luminaries such as Frank Ocean, Beyonce, and James Blake.

He moves through the world like a famous person who does not desire fame. He has a barely active Instagram account, attends no red carpets, drives his own late-model SUV, and does his laundry at a public laundromat near his home. He wants to disappear into the crowd. Find some semblance of “normalcy”. Yet, the disappearing act has only added to his mystique, made his fans hungry for an appearance. He is documented like Big Foot in a series of fan photos–a sporadic presence in films and on television. Then there’s the flute. It’s a whimsical yet quizzical prop that has elevated him from iconic to mythological status.

“André 3000 is just walking around the airport playing the flute” was an actual CNN.com headline in 2019. In 2020, XXL gifted us a compilation of photos and stories of André’s flute-playing “in a city near you.” Anyone worried about how he managed through the pandemic was relieved to see him and his flute through footage captured by a Japanese fan in Tokyo earlier this year.

Does the South Still Have Something To Say?

The product of all that journeying is 3000’s new eight-track album that no one saw coming, New Blue Sun. It’s his first solo project and first release since OutKast’s Idlewild in 2006. In an era of cookie-cutter beats and mindless chart-toppers, André takes an audacious leap into uncharted waters, creating a kaleidoscope of sound that defies classification, he hopes.

In an email exchange ahead of our meeting, André offered insights into the album, which will likely surprise many fans. “It’s much more than ‘André’s flute album.’ Ha,” he joked, anticipating the memes that followed after news of the project dropped. Their general theme: fans twerking, bopping, jigging to soft and airy melodies.

“New Blue Sun represents a continuation of adventure and discovery for me,” he further explained. “I never really know what will come or how I will respond or interpret the inspiration. We all have aspirations, ideas, or plans but isn’t it the most awesome when life surprises us in a way that becomes greater than anything we could have imagined?”

He’s taken a sonic detour, armed with a flute and with a handful of musicians as travel companions. The result is an album that blurs the lines between free jazz, new age, and nature sounds. Yes, it’s completely instrumental. Lyric-less. Perhaps to drive the point home, the album cover art features the image of a blurry André, low to the ground, head down, holding out a large flute toward the camera–offering it up in front of himself.

No bars is a remarkable move for one of rap’s greatest emcees, an artist from whom fans want nothing more than a Word. What we get instead is a score to the journey he’s been on since we last heard from him, from sun-drenched beaches to the cosmic expanse of an Ayahuasca-induced trance. It’s also meant to be a reset from an increasingly noisy music landscape. “We’re the loudest that we’ve ever been,” André argues.

“At one point, the album was called, Everything Is Too Loud,” he says. “But then I just felt like that’s a negative title. You know? I didn’t want to put negative energy out. So I was like, ‘What’s a positive way to say the same thing?’ So New Blue Sun is introducing a new kind of volume, you know? It’s looking past the complaint and trying to figure out, well, what can we do about it?

The product of all that journeying is 3000’s new eight-track album that no one saw coming, New Blue Sun. It’s his first solo project and first release since OutKast’s Idlewild in 2006. In an era of cookie-cutter beats and mindless chart-toppers, André takes an audacious leap into uncharted waters, creating a kaleidoscope of sound that defies classification, he hopes.

In an email exchange ahead of our meeting, André offered insights into the album, which will likely surprise many fans. “It’s much more than ‘André’s flute album.’ Ha,” he joked, anticipating the memes that followed after news of the project dropped. Their general theme: fans twerking, bopping, jigging to soft and airy melodies.

Close Encounters

I spoke with André at length just a day before the in-person sighting. It didn’t feel right to interview one of music’s most majestic figures through Zoom, but that’s how it went down—a conversation with André 3000 via the same platform we use to “circle back” and “touch base.”

When he finally appears on the screen, André is dressed in exactly what he would later wear during the photo shoot; it’s his everyday “uniform,” as it turns out. To my surprise, he looks remarkably regular within the confines of a tiny digital box. He has the easy smile and gentle demeanor we’ve come to know, but smaller in stature and sporting more gray hairs than you’d imagine. He looks like a guy who looks exactly like André 3000 (“I get that a lot,” he says later.) That is until he opens his mouth, and his unmistakable voice pours out—it’s a warm, syrupy Southern drawl.

He’s late for the meeting. “Sorry about that. I had Zoom issues,” André explains. But, after a brief pause, he adds, “Well, I don’t know if it’s Zoom. I might not have my shit together, actually.” Yes, like us, André 3000 blames Zoom itself when he’s late for a Zoom call. But unlike us, he fesses up.

We make small talk, and the conversation feels real little by little, less like an interview and more like a FaceTime with a cousin you don’t see all that often—your favorite cousin who thrills the family when he slips into the function, and who slips out avoiding too many questions and labored goodbyes. Until next time.

I have a million questions: Is OutKast ever getting back together? How’s Badu? Are you dating? Where the hell you been? But those questions only scratch the surface of something deeper, what most fans really want to ask: How are you? Do you miss us like we miss you? The answers, it turns out, are in the music. He’s fine, not “crazy” or lost, just wandering.

“I actually don’t want to stop writing lyrics or making rap songs. That’s not my goal. If I had raps to give, that would be the format.”

That Night

One standout track from New Blue Sun is the third, titled “That Night In Hawaii When I Turned Into A Panther And Started Making These Low Register Purring Tones That I Couldn’t Control… Sh¥t Was Wild,” inspired by a real-life experience.

The tale begins with André’s second night of an Ayahuasca ceremony he attended. Other people were having their experience—crying, vomiting, sweating—and André’s face began to twitch. Before he could comprehend what was happening, his face contorted, completely out of his control, into a snarl with his lip stretched up and his teeth exposed. He had transformed into a panther, an ancient and powerful spirit guide in South American folklore, often said to emerge during Ayahuasca rituals.

“I’m making this purr,” André says, demonstrating the low continuous vibration, “that I’m not doing, that I’m not controlling. And then, at a certain point, it’s actually playing me like an instrument. I’m witnessing this happen like, ‘Whoa, what the hell?’” The purrs were so long that André says he was left gasping for air between them. He was “toning,” explained the shaman there to guide him, creating a vibration meant to shift something inside of him or in the group.

“When I said shit was wild, I mean that,” says André with utmost seriousness. The experience, which he did his best to recreate on the album, was also strangely comforting. Even as he had this out-of-body experience, he was reminded of a long-forgotten childhood memory of a show called Manimal. The show featured a hero who transformed into animals, including a panther, to fight crime. A young André would pretend he was the shape-shifter, curling his fists into paws and skulking around on the ground.

Where He’s Been

Before the album release, the last we heard from André was in the fall of 2017 by way of a GQ profile. His son with Erykah Badu, Seven, had gone off to college that year—a proud moment. However, coupled with the loss of his mother in 2013 and father in 2014, it left André feeling the weight of solitude. He’d also been in a creative rut. “I got to a place where nothing excited me. I kept trying and pushing and pushing. I got to a place where I was just kinda in a loop,” he shared with the magazine.

His arrival in New York City held a promise of change. He carried with him a diagnosis he’d received from a therapist, a social anxiety that had intensified over the course of his career. “I got to this place where it was hard for me to be in public without feeling watched or really nervous,” he said. As the anxiety consumed him, he withdrew, putting off touring, and seeking solace in solitude.

So, he immersed himself in New York City, a place of endless possibility, where you can’t avoid people, but they also tend to leave you alone. It was immersion therapy, “just another word for face that shit,” he told GQ.

Healing

Six years later, he appears to be a healed man—better for sure. “I’m just at a place where I just kind of just deal with life moment by moment,” he says. “Whatever happens, just take a breath, smile a little bit and just, you know, just keep going.”

André credits the Ayahuasca ceremony, in part, for his healing. He says, “I got to a point where I was not wanting to go outside, and it was sometimes hard for me to look people in the eyes. It got to a bad point where—I’m not suicidal or anything, but you can be worse than suicidal, where you’re just kinda walking around, and you said, ‘Fuck it’ already.”

“I came back a completely different person after the Ayahuasca session,” he declares. “I didn’t feel those same anxieties or, if they came, it was always with a smile.”

It’s not for everybody, however, he warns, and not a cure-all. His healing process has also included lots of reflection, hiking, walking, his immersion therapy via New York City, breathwork, and flute-playing. He also credits a move to the Venice neighborhood of Los Angeles, a dreamy section of the city known for its canals, streets reserved exclusively for pedestrians, and a beach full of eccentricities.

A bad day now, “When I feel like really bad,” André says, is when he leaves the studio with nothing to play or think about in the car. “I hate when I feel like the magic is not happening; it sucks for me.” A good day includes painting, drawing, sculpting something in his ceramic class, a few good Zoom calls, a 5-mile hike from his house to Santa Monica, football on TV, and a good meal.

“I think I was put here [in Venice] for a reason,” he reflects. “It was happenstance in a way, but not even happenstance when you look at it on a big scale because I was only supposed to be here six months. ‘I’ll just rent this little house,’ I said, and I kept extending the lease until I was like, ‘I really like it here. I probably need to buy a house in Venice,’ and I just ended up staying. That action helped me to meet all the people that are very much a part of what we’re doing now.”

A New 3000

As the world is introduced to André the flutist, he can’t help but laugh at the various characters he embodies in the public imagination—the “conscious” rapper in a turban, Badu’s crochet-clad baby daddy, the singing rap superstar in a white wig. “I’m very aware, and me and my homies joke about it all the time. We have been joking since 1994 about it,” he says. “I talked to one of my best friends Swift, and he’s like, ‘Man, you know niggas in Atlanta think you crazy walking around with that fucking flute.’ We laugh about it, you know?”

He understands his persona as part his own creation and part the public’s. “They do Erykah the same way. They put a thing on you, but we’re all just growing beings. We experiment and figure out who we are and all that shit. [But,] I understand where it’s coming from.”

“I’m not oblivious,” André adds with a chuckle. “I’m not nuts. I’m not crazy—maybe a little crazy, but I understand everything that’s happening. And I laugh at it. I trip out on it.”

He can take it all in stride because he’s come so far. He’s found the line between performance and expression. The difference, he discovered, is that authentic expression feels good, even if no one is watching or, in his case, listening.

André is excited to share New Blue Sun with the world nonetheless. “You have to be happy to share something; you have to feel confident enough to share. You have to get it to a point where you don’t care what nobody else thinks. It’s almost like a relationship; no one can really judge your relationship.” He wants people to hear the album. “These are bangers,” he says, but his greatest desire for New Blue Sun is that listeners take something from his example. “I hope people will think, ‘Oh, I can just try things.’ I mean, why not?”

There’s another lesson in New Blue Sun about going with the flow or, in André’s case, going where the wind blows you. The practice looks extraordinary in bits and pieces online but perfectly ordinary in context.

I see it at the end of his studio day. André stands outside in a slice of parking lot near the busy street. Passersby stare in amazement at the surreal sight of the rap legend posing against a brick wall, illuminated like a saint by the golden rays of a setting sun and playing the flute. To those people, he appears like an apparition. In reality, he’s just following the lead of the photographer who wanted to catch magic hour. To his credit, André waves to confirm his presence. It’s as if to say, “I’m here with you.” He points his flute and plays in their direction for good measure.