Genetic Imagination

Genetic Imagination

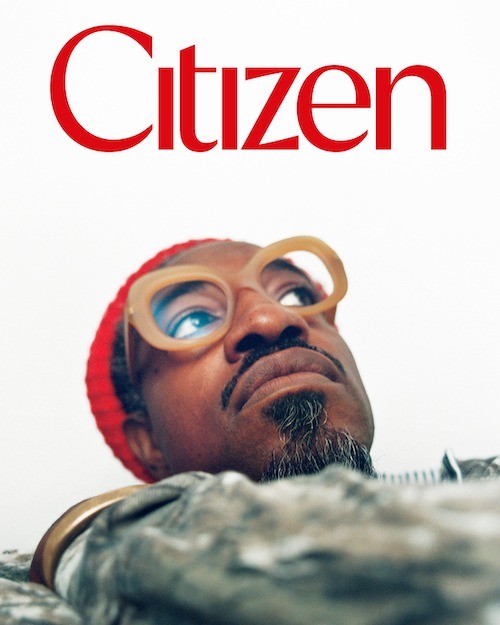

Visual artist Curtis Santiago, on his theory of ancestral joy, the necessity of preserving stories, and what he cares to leave behind

In Conversation Curtis Santiago & Danielle Powell Cobb

Issue 002

Curtis Santiago spent much of 2015 pinching small figurines between his fingers, carefully placing them in vintage jewelry boxes, creating miniature worlds made big by the stories they told. It was this work—tiny dioramas that reimagined known narratives—that Santiago became known for. In the years since he began the work of creating small worlds, Canadian-born Santiago, has moved from the United States to Portugal, to Germany, and now back again to the United States as Artist in Residence at the University of Tennessee School of Art. In the midst of his round-the-world life, Curtis (CS) talks with Citizen’s Co-Editor-In-Cheif, Danielle Powell Cobb (DPC) about becoming a father and how, in these years of shifting and shaping, he has adapted and explored through his work a new philosophy, one that makes room for many futures based on many pasts, one that we might all consider adapting into our own lives and work.

“To me genetic imagination is accessing the full story, the full experience of our ancestors, the joy they experienced, and the dreams they poured themselves into.”

“The future is tomorrow—is 5 seconds from now. Starting to build on those kinds of realities is a necessary act of caring for ourselves.”

DPC: In 2018, you started using and coined, to a sense, the term: genetic imagination. You were using it to describe your work and influences at the time. Can you expand a bit on what that phrase means to you and how it came about?

CS: The whole concept and way of thinking was based on the idea that genetic imagination is an act of self-care. It was a shift in the way I approached my work as a means of deconditioning myself from what was at the time, a traumatic and heavy American experience. I was in the U.S. during the Trump era, during Philando Castile, during Eric Garner, and Micheal Brown. There was a heaviness during that time.

So, the work of just pulling myself from under that weight was very necessary. At the time we were talking a lot about ancestral trauma and all the implications of carrying the burdens and negative experiences of our ancestors. Then, I came across this simple meme that posited that before we were slaves, we were scientists, doctors, mothers, fathers, all these things. And, though it was a really simple idea it really sparked something for me. And, I decided okay, well, that’s what I’m going to dive into. To me genetic imagination is accessing the full story, the full experience of our ancestors, the joy they experienced, and the dreams they poured themselves into.

“It’s always this desire to have Black people love what I do first and foremost.”

DPC: What is the current focus of your work? And how does it speak to this idea of genetic imagination?

CS: Yeah, I think it’s just seeing my parents experience like this Christmas, they came to Germany and we were in Berlin and I took them to Hamburger Banhoffs. And I was first expecting that it was going to be like a 30-minute, 40-minute trip. And then my dad’s going to want to leave.

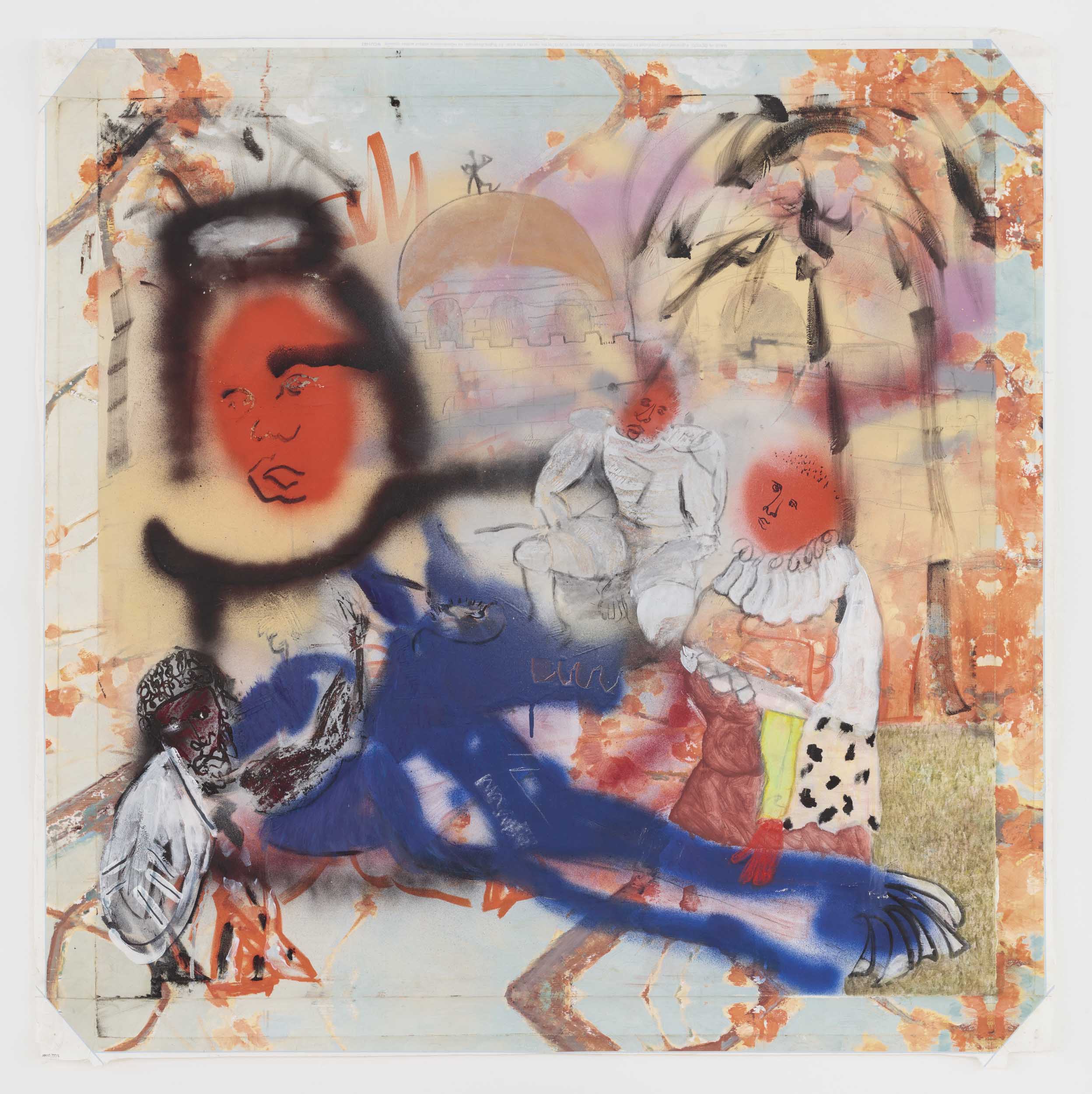

And they’ll just kind of be there to be polite. But they fully dove into the works, like really conceptual works, and showed me a side of them that I completely underestimated or I didn’t even know existed. And so through that and then thinking about their appreciation of art and their exposure to art, I started asking them questions about what Carnival meant to them, like the celebration and masquerade and their dressing up. And then they started telling stories of one specific day, but from two different points of view. My dad is older than my mom. They grew up in a close neighborhood, but they had different peer groups, friend groups, and my mom told the story of that day and my dad told the story of the day. And then somewhere along the line and they’re both talking over each other like Seinfeld’s parents, they meet up in the stories and they start singing this song about jab, jab, about how these steel bands were like the bad boys, the rude boys, and they would fight each other.

That became, my focus, how am I going to bring these stories to the next generation? It has to be through my painting and my visual practice and based on their memories and fantasies, not fantastic fantasies but instead their memories and reimagining of moments as it becomes more difficult for them to remember specific things. When we can’t, we fill in the blanks and things become a little bit more sensational and vibrant and vivid. And so I’ve just really been pushing and asking and digging into their past about their moments of joy. And the genetic imagination idea was a focus on thinking about our ancestors’ joy. So I’m just like moving to a generation that I can get the stories directly from while I can. And then we see what happens after that.

DPC: Thinking about genetic imagination and the idea that we can reach back and access the happiness and the joy of the people who come before us, what would you want future generations to be able to hearken back to from your work

CS: As much as one can be free in this system, I’ve had a lot of freedom. Freedom. No one told me what to make to get into a gallery, no one told me that I couldn’t travel and get up and go when I wanted to go. So, I would first want future generations to see someone who did it differently but also did it the same. That took a certain amount of freedom for themselves but also, like my parents, worked hard and constantly worked on building confidence and faith in myself.

“It’s always this desire to have Black people love what I do first and foremost.”

“I want to love [my work] more than most. I want to be proud and love it and get joy from it from looking at it, even though the process isn’t always joyful.”

DPC: Yes, we see what happens after that. I could imagine that a pretty nuanced critique of genetic imagination or this idea of focusing on ancestral joy is this idea that would diminish or tend to dismiss, all the atrocities. What would you say if that was someone’s critique?

SC: At first, I would have to ask who’s critiquing because it’s impossible to live in a black body, let’s just say a black body because there’s been many groups of people who’ve gone through suffering. But for me to live in my body, it’s impossible for me not to think about the traumas and experience the traumas. I’m in the American South where every interaction I have to have, I have to analyze, am I safe?

It’s omnipresent.

I was reading the other day–like, if I just start laughing my brain starts to produce a chemical that tells my body that I’m happy, even though the expression starts as fake joy. If I’m thinking, oh, right now, I’m in Portugal and I can see and feel the sun, my brain doesn’t know that I haven’t necessarily been to that spot yet. These ways of thinking generate more joy and generate more possibilities for an imagined future. Which I think is an essential part of Afrofuturism. It’s not necessarily Star Trek. The future is tomorrow–is 5 seconds from now. Starting to build on those kinds of realities is a necessary act of caring for ourselves.

DPC: Who are you making your work for?

SC: For my son, to provide resources so I can give him the things that I dream of giving him financially, but also life experience. From my upbringing, growing up outside of major Black communities, it’s always this desire to have Black people love what I do first and foremost. I want them to see themselves in what I do. Even though there is no monolith. There’s still a thing. I don’t know exactly what is is. But, it’s a spiritual thing.

DPC: Right.

CS: Then I want to love it more than most. I want to be proud and love it and get joy from it from looking at it, even though the process isn’t always joyful.

Ultimately, I just have to be authentic to myself, this mix of many, many things. I love looking at fantasy. And obviously, Octavia Butler is super on-trend right now. For obvious reasons, her work couldn’t be more relevant. But if you look at what was just her imaginings in the ’70s you think about how helpful it might have been for her to tell stories that now we can kind of understand a bit more. I’m hoping that by dealing with fantasy and the subject matter I’m diving into now, that, when time goes by, my work will kind of separate itself to some degree from current trends.

Artwork by Curtis Santiago