Out of the Trojan Horse

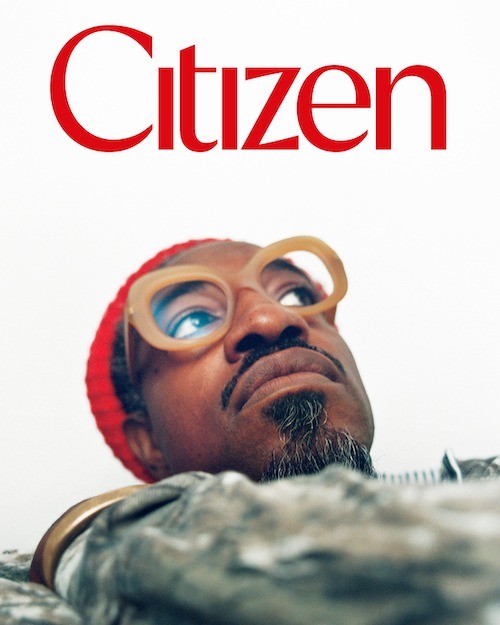

Photography by Fenn O’Meally

Issue 003

Breakbeat jungle pioneer Goldie offers photographer Fenn O’Meally his thoughts on what to do when you get behind the gates.

“When you run in with your Trojan horse, whenever you get out don’t take anything as given because you’re not here for that long…Keep the hunger.”

Clifford Joseph Price, known to most by his mononym, Goldie, exists in the rarified space in music culture reserved for someone who is the favorite of your favorite. He is a cult cultural figure–a representative of an era, an idea, a culture. Most noteably, Goldie is often credited with popularizing drum’n’bass and UK jungle music during the mid-1990s, bringing them to the same popular standing as techno had become by the early 90s. In the mid-90s, Goldie, with a full mouth of gold teeth, hair shaved low to his head, and bleached blond, represented a new era. It was an era of transformation, in which those who produced and released albums but did not perform the music and had traditionally been only names displayed behind acrylic CD cases became larger-than-life personalities recognizable outside of the studio and the club–icons in the most literal form of the word. During his lifetime, Goldie has fulfilled the main tenet of what it means to be an “icon,” crossing the lines that divide the creative worlds of art, music, film, and fashion.

“I remember when Busta Rhymes and Public Enemy came to The Hummingbird in Birmingham, and Flava Flav turned up on a unicycle on stage, and everyone lost their fucking minds.”

Raised in Wolverhampton, United Kingdom, just northwest of Birmingham, Goldie was born to a Jamaican father and a white British mother of Scottish descent. At the age of three, he was put up for adoption and raised in childcare homes and by several foster parents. Goldie was led to music while seeking a people and a culture he could connect with and call home. “When I say my people, I mean people with the same skin as me that lived on the estate,” Goldie explains. “I would run away from the children’s home to go and find my people, to go skating, to go and listen to soul music,” he continues. “It’s like when a girl finds a boyfriend, and they run away together. The girl was the scene.” In the early 1980s, Goldie wore his hair in dreadlocks, and the community where he found a sense of home gave him the nickname “Goldilocks.” When he cut his dreads, “Goldilocks” became “Goldie.”

Through the scene and the culture that influenced it, in 1982, at the age of 17, Goldie found the artistic expression of graffiti, “I found culture in a book called Subway Art published by Thames and Hudson. More copies were probably stolen than bought,” Goldie explains. “When I opened it up, it just changed my life forever.” Goldie would go on to gain widespread exposure for his work as a graffiti artist. Influenced by time spent in New York City among the intertwined movements of graffiti artistry and hip-hop, Goldie’s works of graffiti in the UK became recognizably his. By 1987, his work would be featured in Spraycan Art, a follow-up to the book that originally inspired him and documented the worldwide spread of New York’s graffiti style and subculture.

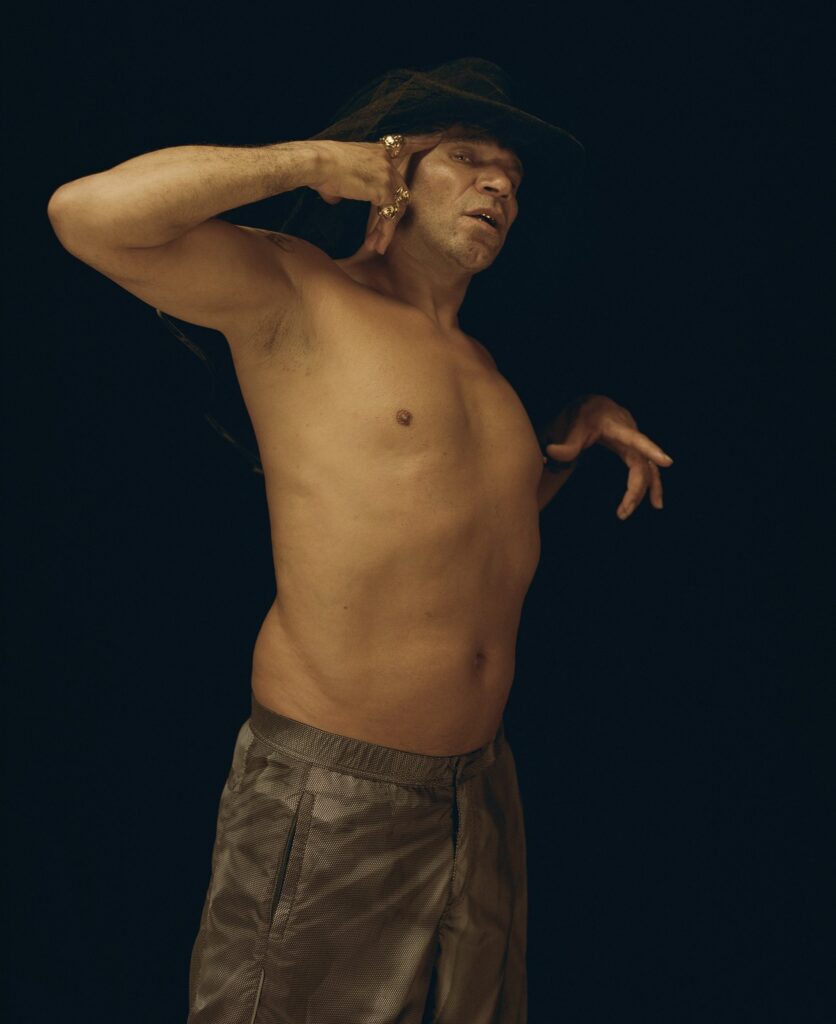

“Coming at the end of this tour has been a lot of energy, and to have this energy at 58 is a lot. I can’t just give you 100%; I’ve got to give you 150%.”

For someone informed by the cultural movements coming out of New York City’s Bronx and Harlem neighborhoods during the late 1980s, it makes sense that Goldie next turned toward making music. Beginning in 1992, Goldie released a variety of singles under the pseudonym Rufige Kru. Then, in 1994, he co-founded the now legendary music label Metalheadz and the subsequent club night Metalheadz Sunday Sessions. With Metalheadz, Goldie released several albums under his name, including the critically acclaimed 1995 album Timeless. Considered by many to be one of jungle’s first and best full-length albums, Timeless entered the UK charts at number 7.

Now, at 58 years old, Goldie’s work and image have entered the mind of the zeitgeist. Today, the image of the self-proclaimed “eighties boy bought up on the shoulder of giants within street culture” is archived in Britain’s National Portrait Gallery. He also wears “MBE” behind his name, having been appointed ‘Member of the Order of the British Empire’ for his services to music, the arts, and young people in 2016 by the late Queen Elizabeth II.

Goldie likens his current space in our official cultural record and the position of Black music and culture of the late 1980s and 1990s to a “trojan horse” that penetrated the walls of the larger culture. The larger culture sought not to recognize the value of the people behind the music and the art they were consuming and the trends they began to mimic. But, through their artistry, the people were already behind the gate. For Goldie, artistry is transcendent in this way. “I’m an alchemist trying to make his finest alchemy,” he says when asked to describe himself.

The day Goldie arrives at a studio in London to shoot the images for his Citizen cover story, something powerful happens as he and photographer Fenn O’Maelly find an instant chemistry–a sort of seeing of themselves in each other. They discover that they are variants made up of many of the same ingredients. Fenn is also of Jamaican and British descent, raised just outside of Birmingham, and, like Goldie, was thrust into a creative work by the desire to connect with others. Each seeks transcendence in their own way. And, in the conversations between the two on set, Goldie is morphed into a tender figure, a guru of sorts, set on imparting a kind of caring wisdom.

In the following conversation, recorded two weeks later, Goldie from his second home in Thailand and Fenn, on the move in Paris, talk about what to do once the hype finds you and you find yourself behind the city gates.

G: Yo.

FO: Hi, how are you?

G: I’m good. I’m trying to have a sabbatical.

FO: I’m in Paris; it’s a crazy day. Sorry, I’m going to have to hop off soon and hop into the car.

G: Can I ask you something?

FO: Yeah, go for it.

G: How was your relationship with the camera? Was it just going through the biscuits, as I call it, or was that relationship something more?

FO: I think what was so special about even the short amount of time we spent together was I felt so privileged to be in a space with somebody I connected with so quickly and effortlessly. Days like that day remind me why I found myself with a camera. The camera was a way to connect to people, or I guess, an excuse to connect to people when the courage I had within myself wasn’t there.

I grew up just outside of Birmingham in a small town. And, looking back, though my friends were wonderful, so wonderful, I had so little in common with them. My dad was Jamaican, my mom was white British, and my home setting was just very different from the homes and worlds that my closest friends were brought up in. As soon as I found the lens and as soon as I found filmmaking, I just found this love for connecting to people and humans and life. And I think it was that that really made me feel very connected to filmmaking and very connected to photography.

G: I was kind of socially awkward as well. I know where you come from. Birmingham, that’s no joke for a young fly girl like yourself. You’ve got a lot of energy coming at you. For me, I remember wanting to be like my friends, my brothers, robbing people and just hanging out. We were all Rastafarian, but we were robbing people. So I was in a conflict already. But I had to keep that conflict to myself because you’ll get your head kicked in. But then I would go and get changed and put my paint clothes on; I would paint a piece on the estate and ignore everything else. So there was this awkwardness in that I just wanted to paint.

In one of my first conversations with Virgil Abloh, we spoke heavily about alchemy and about the Trojan horse. I feel it’s all been like repatriations in a way with how finally, even with Virgil, there was this recognition of street culture. For my generation, our job was this very difficult navigation of culture, and we had the task of rolling the Trojan horse through and getting out. And, now that we have rolled it in far enough, it’s very difficult for them to get rid of us.

Virgil and I really hit it off, and we pinched ourselves, saying, “Where are we?” “Is the game up?” A massive part of him wanted to put a light on where we come from. And it always fascinated me that he wanted to do this whole Metalheadz collaboration. He felt the club was important. When he posted a picture of an Off-White trainer on top of a Metalheadz box set, it was as if an escalator stopped. When an escalator stops, part of the human condition is that we find it very difficult to walk on because when it stops, your body tries to adjust, to walk forward, or to start climbing, but it takes some time for your brain to adjust to the sudden change. The point I’m trying to make is that it was a very awkward moment for me to accept that the walls had been brought down and that what we had been doing all those years ago was considered culture. I remember when Busta Rhymes and Public Enemy came to The Hummingbird in Birmingham, and Flava Flav turned up on a unicycle on stage, and everyone lost their fucking minds. We’ve had these glimpses of heroic moments in the UK when this stuff happened, but now those walls are down, we’re in this world together where anything is possible.

But maybe now, we need to remind ourselves how we built the Trojan horse and consider whether we need to move it or position it slightly differently. You know what I mean?

FO: Yeah, yeah.

G: Fenn, I think you’re going places in a lot of different ways, and I think wherever that’s going to be, I think it’s going to be a really beautiful universe where you are creating and constructing. It’s great to see someone so young coming from a place just down the road from me moving into the beautiful universe.

FO: Wow, thanks.

G: Well, for me, coming at the end of this tour has been a lot of energy, and to have this energy at 58 is a lot. I can’t just give you 100%; I’ve got to give you 150%. I need to make sure it just goes all the way until the wheels fall off. And that’s how it’s got to be when you’ve been around for so long. It’s what people expect. In the UK, people don’t really protect the OGs–let them slow down and just admire them for what they used to be.

FO: Biggie has this line, “My slow flow is remarkable,” and there’s something that really speaks to me in that line. It’s really about what we’ve lost over time, or at least what I feel we’ve lost in the modern day– the ability to feel and to be able to connect and be able to have space to make art. Now, so much of art is constant regurgitation. And, I think if you really appreciate art or if you really appreciate where a certain piece of art comes from, the need for it to be fast-paced, the need for it to be like the thing that is hot right now, the need for it to latch itself to a trend falls away.

G: The bottom line is you’ve got to stay outside the realm of time because my quote is, “A truthful idea lasts in the honesty of time.”

FO: Right.

G: I always remind myself of that quote. It’s important for any art form. Because it’s not just how cool it is, how it’s been laid down, you should look at it and say, “Are these lines true to what I want to do? Is this cut, this material, right? Is this bar going to be the right bar to lay down?” Why does Biggie still sound so dope? It’s the way that it’s put together. In a way, the same shit was happening then that’s happening now. But the dialect has changed to be about the Lamborghini and the girls. It doesn’t make any sense to me.

FO: Yeah. I think it’s interesting because, in the same way, Andre 3000 talks about how, during the early days of creating, it was like he was creating in his bedroom–a kid playing with his toys, and as soon as the door opens and his mom watches, he stops playing. We need that room to play, that kindness, and allegiance to self alone.

“When [the hype] comes, when it’s all around you. You’ve got to be able to cut yourself off from it.”

G: One thing I want to leave you with is–God bless you, you’re so young, you’ve got the world in front of you–you’ve got to remember that when you run in with your Trojan horse, whenever you get out don’t take anything as given because you’re not here for that long. Fenn, keep the hunger. You’re going to go places. Don’t be influenced by the money. The money is nothing. The money comes and goes. You’ve got to remember that stuff is perpetual. It just moves. And we just got to remember, you’ve got to get out there and do what you do, to be the best you can. And when the tide comes, just get out there, man.

FO: Yeah. The hype doesn’t make me feel good. What makes me feel good, what makes me thrive, is the work that I connect to rather than the hype.

G: I like that. But remember that when it comes in, it’s all around you. You’ve got to be able to cut yourself off from it. If you forgot money and had to do one project right now, what would it be?

FO: What would it be?

G: Any budget you want.

FO: I think it would probably be something in Jamaica having to do with my roots. Maybe it’s a film about my dad in Jamaica. My dad hasn’t been back to Jamaica for a long time.

G: What’s crazy about that is how it shows this innate desire to look back and find something about our parents or family. I think people like us want to search.

FO: Yeah, for sure, for sure.

G: I’ll wrap it up. Listen, it’s been a great time.

FO: Thank you so much. When are you back in London?

G: I’m not back, probably until June. I’ve got a show I’m putting together; it’s all [imagery of] arrows, which I’m doing at the moment, and it’s–

FO: Arrows?

G: It’s about direction, and they’re all three-dimensional crazy bits and stuff that I’m doing at the minute. But yeah, it’s just loads of work that’s based on images. I know images interest you. These images are all based on my life–collage.

FO: Wow.

G: Where are you going now? You’re off to another shoot?

FO: I’m off to a meeting now. I’ve been in and out of meetings today.

G: Well done. Well, listen, love and light, man.

FO: Lots of love.

G: All good. And have a great Christmas.

FO: You too.

Credits

Photography: Fenn O’Meally

Stylist/Fashion Director: Juanjose Mouko Nsue

Photo Assistant: Pedro Faria

MUA: Viktor Taylor

Movement Director: Jasiah Marshall

Management/Production: Sarah Mahini, Izzy Daviss, Anaïs Maurel c/o Phenomena Photos

Venue: Earth Hackney

On Set Producer: Natalie Tuffuoh

Art Director: Jack Foreman

Special thanks to Paula Karaiskos @ Storm Models