I’m Still Here

I’m Still Here

Nikole Hannah-Jones, creator of the 1619 Project, talks with Patrice Peck, publisher of Coronavirus News for Black Folks

Introduction by Danielle Powell Cobb

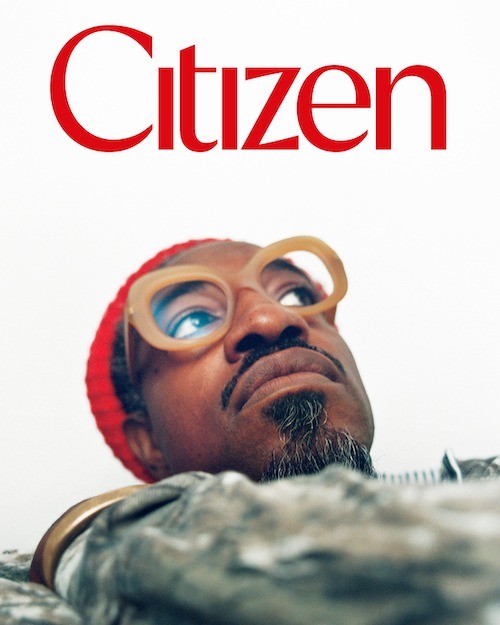

Photography by Myesha Evon Gardner

Issue 001

NIKOLE Hannah-Jones is no stranger to being questioned. Perhaps this is why when she appears on a computer screen, she bears the posture of familiarity. It is late December when we log into a Zoom call joined by Patrice Peck. Nikole is wearing a white sweatshirt with the words “all my life I had to fight” printed on the front and leaning forward into her computer screen, comfortable and unarmed. Her hair is a shade of red that could only be chosen by its wearer rather than given by some coincidence of DNA and though I have met her in passing several times and seen her on TV often, there is something new and known. She is home, she is soft. She is informal and unguarded as I introduce her to Patrice. Her hair is up in a loose ponytail, and some wisps have fallen around her face. When she talks of her daughter, she smiles as she speaks, and she listens patiently as Patrice begins to ask her questions. About five minutes into their conversation, I log off, introductions have been made and Patrice is a competent journalist fully capable of conducting a well-rounded interview of Nikole. But, what I realize in those first few minutes is that Nikole is an entire constellation that has only been seen by many, including myself, as a star or two.

What is known to many, what is seen bright and visible to the naked eye is that Nikole is a black woman. She is a fair-skinned black woman often seen with ringlets of fiery red hair framing her face. She wears bold red lipstick at times and eyeshadow in deep hues. She has a full bust and full hips, and she does not hide her body (her only request with regard to the photoshoot that accompanies this piece is that we not dress her in ill-fitted or baggy clothing). She is a journalist who over the last four years has written long form narrative journalism for the New York Time’s Magazine. In 2019, she created, produced, and edited the 1619 Project, introduced as an issue of New York Times Magazine that sought to place “the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of [the American] national narrative.” In 2020, Nikole received a Pulitzer Prize for her work on the Project. This, the 1619 Project, then the Pulitzer that followed, propelled her into a reluctant celebrity of sorts.

Journalism is rooted in the discovery and presentation of truth. But what happens if you are a journalist whose work explores a more inclusive story that challenges long-held truths?

“I think we can make certain truths undeniable to a large segment of the population that has not wanted to learn these truths. That’s all I’m trying to do.”

To illustrate the magnitude of the Project, consider that upon its release, readers began to travel outside of their neighborhoods and cities simply to get their hands on a physical copy of the magazine. In those first few weeks, there was a niche genre of social media posts featuring photos of the magazine captioned with some version of “I got my copy!” On the day that Patrice sat down with Nikole, one could find copies of the magazine and the accompanying newspaper insert on sale on Ebay for up to $500. Consider that the year 1619 entered the common American lexicon for the first time after the Project was published and that out of the Project came two podcasts, educational curricula, a 7 book deal, and a film development partnership with Oprah Winfrey’s production company. Flowing from the Project there was fanfare, live events, and even counterfeit 1619 merchandise.

Then came the critics.

First came a group of historians. Princeton history professor, Sean Wilentz, in a letter signed by four other leading historical scholars, requested that the New York Times issue corrections to the Project due to “factual errors and the closed process behind it.” They argued that the proposed errors suggested “a displacement of historical understanding by ideology.” Jake Silverstein, editor-in-chief of the Time’s Magazine, responded to Wilentz’s letter, defending the Project’s reporting, and declined to issue the proposed corrections.

It is important to note that no black historians signed Wilentz’s letter. Nell Painter, a leading historian and professor of American History at Princeton University, was asked to sign her name to the letter but declined to do so. In statements made to Adam Serwer at The Atlantic, Painter admitted, “the 1619 Project was not history ‘as I would write it.’” She explained however that for Wilentz and his colleagues, “true history is how they would write it. And I feel like he was asking me to choose sides, and my side is 1619’s side, not his side, in a world in which there are only those two sides.”

Next came criticism by conservative media personalities arguing that the Project was a “propaganda campaign on race” (Newt Gingrich), “ahistorical” (Tucker Carlson), “the stuff of totalitarian regimes” (Cal Thomas), and generally unpatriotic. Then, on the heels of right-wing pundits, blasting the content of the Project as “deceptions, falsehoods, and lies,” was the then President of the United States. In remarks delivered to a crowd on September 17, 2020, The 45th President stated that the 1619 Project sought to rewrite, “American history to teach our children that we were founded on the principle of oppression, not freedom.” Which to the thinking person immediately draws the questions: Who is to be included in that conception of “we“?

“I frankly don’t believe in just letting people disrespect you, and you just silently take it.”

Then, over a year after the Project’s publication, in an extraordinarily rare allowance by the Times, Nikole‘s colleague, Bret Stephan dedicated almost 3,000 words, in the Time’s Sunday Edition, to the opinion that the 1619 Project though “ambitious,” was a “failure.” All of this, the work and the controversy surrounding it, came to be the thing, the brightest and blinding story attached to Nikole.

Accordingly, what is also known about Nikole, is that she Tweets under the handle @IdaBaeWells. When I first talk to a friend about commissioning an interview of Nikole, my friend quips that her niece—a black gen-z teenager living in Georgia—talks of Nikole as though an internet character on to herself (“IdaBae!”), referring to her by her Twitter handle and never her given name. In this way Nikole’s social media self is a whole other way of being seen, a character partly disembodied from work and from her physical self. Well, it was.

What is also known of Nikole by those who followed her on Twitter then is that @IdaBaeWells would come for you if you sent for her. In other words, more universal ones, she did not shy away from defending herself or her work, nor did she mind vehemently debating others on an almost daily basis. In my almost four decades on this earth I have always known that this for a black woman is the slipperiest of slopes. That debating out loud and in public will ensure that adjectives like “arrogant” and “angry” are often found in close proximity to your name, that this kind of sureness, more often than not comes tied to a persistent and expressive hatred.

At the time of Patrice’s interview, Nikole had just over half a million followers on the platform and had tweeted close to 21,000 times since joining the platform in March 2009.

Then in close succession, these things happened:

Nikole was accused of “doxing”—publicly posting another person’s private information without their permission—when she tweeted out a screenshot of an email from a conservative media reporter that included his phone number. After an onslaught of conservative media uproar she deleted the tweet and the large majority of the rest of her tweets. Then, as it seems to be a sort of rite of passage in 2021, she announced she would be taking a break from the social media platform altogether.

As the second wave of COVID-19 settled in, conservative media’s seeming obsession with Nikole waned. Unitl, it was announced that she had been offered a tenured position at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, her alma mater. Then, it was announced that in a stunningly rare, if not unheard of, turn of events, she had been denied tenure by the school’s board of trustees, though she had the full support of both faculty and administration. After threatened legal action and widespread debate, and outcry from the academic community, UNC reversed course and offered Nikole tenure.

Nikole declined. She instead announced, sitting across from Gayle King on national television, that she had accepted an offer, with tenure, to teach at Howard University, a historically black university or HBCU.

“I frankly don’t believe in just letting people disrespect you, and you just silently take it.”

Journalism is rooted in the discovery and presentation of truth. But what happens if you are a journalist whose work explores a more inclusive story that challenges long-held truths? What if you are a black journalist and a part of the group that desires to be included? Without fail, your objectivity, your ability to remain impartial and subsequently truthful, will be called into question, a questioning that allows the questioner to never reckon with the truth but only to address the perceived appearance of impropriety.

Though so much of this had yet to happen when I sat down to introduce Nikole (NHJ) to Patrice (PP), Nikole home and her body leaning in toward the camera, I found then that I wanted to mimic her, both in purpose and in “ambition,” I wanted to hear about her alternative narrative, the truth, or the truth as she sees it.

PP: A lot of black writers or creatives experience a condition of double consciousness and this consistent contemplation of varying how they present themselves in different spaces. How has duality played a role in your own personal and professional life? Have you embraced it, denouncing it, or even just witnessed it?

NHJ: Yeah. I would say I very consciously try to avoid that. I mean, clearly, I don’t engage in a professional setting the way I would engage when I’m hanging with my friends. But in how I choose to look, wear my hair, how I talk, jewelry, just everything about my aesthetic is very uniform no matter what setting I’m in, and that’s very intentional. I think it’s important to send a message that intellect and talent, and ability has nothing to do with your own personal style or cultural style. I mean, you come across professional Black people in one setting, and then it’s like you see the relaxed true self outside of that. And I get where it comes from, but it’s just not something that I’ve ever really chosen to engage with. I think there have certainly been times in my career where it has hurt me. But, I think that having to compromise the essence of ourselves actually chips away at your soul, and it’s not a compromise I’ve personally been willing to make.

PP: People at this point are so familiar with your work, but you’ve been in the game for a minute. You were just mentioning how remaining your authentic self has sometimes hurt your career. Can you point to an instance where showing up unaltered has harmed you?

NHJ: Yeah, sure. About eight years ago, I almost left journalism. I was working at a newspaper on the West Coast. I had been hired, as I was told, because I wanted to write about race and racial inequality. But once I got there, that’s not what they wanted me to do. I was told that my ideas for stories, the types of stories that I wanted to write, writing about Black people, in particular, was limiting, and it was a sign of my bias and that it was going to hold me back.

I think there’s a lot of pressure. I think it’s getting to be less so, but still pressure on Black journalists to leave the Black part off. And if you define yourself as a Black journalist and say, “I report through a Black lens,”–even though white people don’t define themselves as white journalists but are clearly reporting through a white lens–when you do that, that is seen as a negative, and gives people an excuse to try to discount your work.

At one point, I was called into the office and talked to about the way that I dressed. I was 30-years-old, and to have another grown woman who was a higher-up editor call me in and tell me that I was not dressing professionally enough was pretty astounding. It became clear to me that everything about me was somehow offensive, right? Like the way that I dressed, the type of stories I wanted to do. Newsrooms want diversity of phenotype, so they want to be able to check off a box and say we have a Black person. And, they want us to come into these spaces and then not assert that Blackness in any way. I only got into journalism to do a certain type of work. I’ve done all types of reporting, but to be told that I could not, or I would be punished for wanting to write about race, I almost left the industry. And, really, the only reason I didn’t leave the industry was that I could not actually think of anything else I wanted to do with my life.

PP: In 2016, you mentioned wanting to go back in time and not have put yourself into a particular piece. Were you talking about the school segregation piece you wrote for the New York Times, “Choosing a School for My Daughter in a Segregated City?” and incorporating your personal experiences? How do you feel now? Are you still regretful?

NHJ: I came up as an old-school reporter. And I wasn’t a magazine writer. I never had a desire to be a magazine writer. That meant you don’t spend time reporting and excavating your own life. Transitioning into more of that type of writing was a hard kind of mental shift for me to make.

But I don’t feel that way anymore. I’ve become much more of a magazine writer. And, I think I have come to use that form in a powerful way. The way that people responded to me doing that piece, in sharing my family’s own struggles with living up to our values–I just don’t know that the piece would have gotten the same response and, people would have internalized that I was talking about them without kind of doing the personal narrative. But it’s been a shift in my career and how I see myself and my journalism for sure.

PP: What really actively led you to reporting in the first place, that seeing yourself as a journalist?

NHJ: Yeah, yeah. I was a weird nerdy child. I got my first letter to the editor published when I was 11 years old, and I was writing about Jesse Jackson’s primary run in 1988. [Laughter] Who the hell does that at 11 years old? I just always remember being really interested by the news and really interested in history, and from a young age, having a very strong sense of injustice, always feeling the need to root for the underdog, and understanding Black people as underdogs in our society. I was bused into predominantly white schools. Once, I was just complaining to my black studies teacher about our high school newspaper. He told me I had to join the paper or shut up. He said that if I didn’t like how the paper portrayed kids like me, then I had to write those stories myself. Something just kind of clicked in my mind. I did join the paper, and I came to understand the power of crafting your own narratives, that it’s not enough to just sit and complain about coverage. But that, we have to be in the room shaping the coverage.

PP: Got it. And, so–

NHJ: Can I say one more thing? I’m sorry. So I always read the crime logs in the paper, and I read the crime log because I was always looking for people I knew in the crime log. The black population in my hometown was really small. And Iowa has one of the worst racial disparities in incarceration in the country, which I didn’t know at the time, but I just knew that people I knew were in the crime log. So, it was these little connections that I was starting to make in my head. Also, the experience of being bused into white schools from the second grade gave me a different education. I could just see the white kids at the school are not smarter than me and their parents don’t work harder than the people I know back home, but they certainly were different types of jobs, and their houses are nicer, and everything about what they had was nicer, but they didn’t have a stronger work ethic. I think those very early experiences just led me to question the narratives about why things are like they were.

PP: No. I’m so glad you added that. Clearly, from a young age, you’ve always been thinking very critically and questioning what–

NHJ: I was weird. I’m telling you. It paid off, but it was a struggle childhood to be that weird-ass nerd. Trust me.

PP: Laughter. In a previous interview, you mentioned not being from prestige. You’re from Mississippi sharecroppers? And, I think it’s so interesting that you talked about this critical lens that you had and how much of your upbringing influenced that critical thinking. How did your upbringing influence you as a journalist?

NHJ: Yeah. Everything about my life is a surprise. I don’t want to say there weren’t expectations. The expectation was we would go to college. The win was going to college. I started working when I was 13 years old. The very first job I had was passing corn in the summer which is the closest thing you can experience to child slavery. You’re out in the cornfield for 12 or 13 hours a day in 90-degree weather, working in a field for about $4 an hour. But I was determined that if my parents couldn’t buy me the school clothes I wanted, I was going to work for them. I worked two jobs until I was 30 years old. I was a newspaper reporter and selling mattresses–and I had a master’s degree. So when you come from that–it’s just always very grounding.

I’ve said that my greatest regret in life is I didn’t go to Howard, but I didn’t go to Howard because I didn’t even know there were Black colleges. My family that migrated to Waterloo were sharecroppers. They were not educated Black folks from the south. They were Black folks from the south who didn’t even finish middle school. At the same time, I’m biracial and so I was growing up with the White side of my family, and my White grandfather was a union man that worked in a factory.

My mother’s father and my dad’s mother were both born in 1924. My father’s mother was born a Black girl. And I think because of that, I was always led to question all of the things said about society and understand how all the things said about black people aren’t true. And I can compare directly in my own family.

And that’s always shaped my skepticism about these narratives.

PP: Considering that you are not new to this, reporting on those topics, what has been the toll on you personally–emotionally, mentally?

NHJ: So, I really can’t imagine doing anything else with my life. When I did The 1619 Project, sitting nine months in slavery, in the institution of slavery, and just thinking every minute of every waking hour about the brutality and what we had to go through, that certainly did take a toll. I was drinking a lot. I was not eating healthily. I cried a lot. That was really hard. But, I think, overall, I just feel grateful to be able to do the work that I do. I think a lot about my grandmother. First, she was a sharecropper, and then when she moved up north, she was a domestic and a janitor. I’m like, “That’s real work. That’s hard work. What I do, it’s a privilege.” That’s really how I feel. It really is.

PP: Do you feel that people have a really clear sense of who you are, given that you are very vocal on Twitter, and like I said, like you say, you keep it 100. You present yourself as it is, and so, do you feel that people have a sense of who you are?

NHJ: People who don’t really know me personally?

PP: Yes.

NHJ: No, I don’t think so. I mean, yes, I’m very fiery. [laughter] I am a person who doesn’t really suffer foolishness, but I’m also extremely sensitive. I care a lot. The issues that I write about, the work that I do, I care deeply about it. I never expected anyone would know my name. I just wanted to be a newspaper reporter who wrote about black folks in the south. That was really all I wanted to do. And everything else has been a shocking bonus. Sometimes people don’t really understand that this work has only ever been about the work. I think what people also don’t get is, again, because I don’t come from pedigree, we just play by different rules, right?

And I know everything that I had to do in order to get into the space. I’m 44 years old. I didn’t have overnight success. I’ve been doing journalism for almost half my life. So when people are trying to discredit the work, I take it very personally, and I frankly don’t believe in just letting people disrespect you, and you just silently take it. That’s not my form of engagement. But, I’m not in Waterloo anymore. So I think people don’t always understand. They think that I’m responding that way because I think I’m better than people. I’m responding that way because I’m just so used to people trying to disrespect my work and me and people like me that I feel I have to stand up.

PP: Do you ever feel like you have to pick your battles now?

NHJ: Yeah, for sure. I mean, I 100% have regrets about some of the ways I’ve engaged with people who have criticized the 1619 project and particularly how I allowed myself to be baited into responding the way that people who just wanted to discredit the Project wanted me to respond. So I certainly have– I don’t engage nearly as much on Twitter as I used to. I’m much more conscious of how I engage on the air because I do think that I’ve played into the hands of people who didn’t want the 1619 project to exist, don’t like that there’s a Black woman like me in this position at the New York Times. And I haven’t always done myself or that work justice, and a very good, dear, dear friend to me was like, “You’ve created this thing. Do not let these people draw you into something that actually hurts the work that you produced.” And this is again where you kind of have career dysmorphia because in my head, I’m still the anonymous chick with 300 followers, and I can say whatever I want, except that’s not who I am. And it’s taken me a while to really figure that out. I’ve always tried to use whatever power I have for the positive in terms of– I started the Ida B. Wells society. I try to be a door open or even with a 1619 Project, everything that’s coming out of this is me also trying to ensure that I am creating opportunities for descendants of slavery in particular. So I also try to do that. But I realize that I just have to be much more careful and not do things that are detracting ultimately from the work that I’m trying to do and the mission that I have. And some days, I’m better at it than others.

“Mama, if you quit, you’ll be KO.” And I was like, “I’ll be knocked out?” And she was like, “No. Beaten.”

PP: Definitely.

Okay, so let me know if you’re comfortable speaking on this or if you want to go off the record. One of your colleagues at the New York Times very publicly challenged the reporting and validity of the 1619 project. Did that make you reconsider your future with the Times. Because me personally, as a fellow black woman journalist, I felt a kind of way, I felt disrespected, and I’m not even you.

NHJ: Yeah. I mean, I’m not going to go off the record. I just, in general, feel like we should just be honest. It was devastating. And, I did think about whether the New York Times was still going to be the right place for me and my journalism after that happened. But honestly, it was something my daughter said to me, my 10-year-old child, which makes me proud because clearly, I’m imparting some type of wisdom to her. She overheard a conversation that I had when I was contemplating how I should respond. I was taking her to school, and she said, “Mommy, don’t those people want you to quit?” And I was like, “Yeah. I mean, yes, of course, it would make them happy.” And she said, “Mama, if you quit, you’ll be KO.” And I was like, “I’ll be knocked out?” And she was like, “No. Beaten.” And when she said that, it almost stopped my heart, and I was like, “She’s absolutely right. So that was when I made the decision. I wasn’t sure what I was going to do, but I was like, “If my child who I’m trying to raise a certain way, my black daughter, feels that I will have let these folks beat me by doing that, I can’t do it.” So, that’s ultimately what the decision came down to. So, I’m still here.

PP: “Still here.” Laughter. I love that. So, the work of 1619 continues. The platform is growing, becoming multi-platform. What has that been like? You’re working on the TV show. You’re working on the book. What can people come to expect?

NHJ: Yeah. It’s been an amazing journey. When I pitched the Project, I had no idea it would become what it’s become. Right before publication, my husband can tell you I was wracked with anxiety, almost paralyzing anxiety. This can come out and nobody cares, nobody reads it, and I’ve commanded all of these resources. I’m going to not just close the door for myself, but for everyone, every black person, brown person trying to come behind me. There was nothing to make me think that if you told this in an unflinching, honest way, that a country that’s been in denial about the legacy of slavery for all this time would embrace it. So it’s just grown into this thing of its own, which I hope has shown newsroom and TV executives that if you tell these stories truthfully and unflinchingly, and if you respect the intelligence of the reader or the viewer, people will take to it. Right? You don’t have to produce bullshit, and you don’t have to produce black stories that are palatable to white people. It’s okay to make people uncomfortable. So yeah. We’re expanding the 1619 Project. We signed a seven-book deal. In 2021, we have a children’s book as well as an adult book coming out. We’re working on a docuseries and scripted [content]. I’m just trying to create as many opportunities for black folks to tell our stories the way that we’ve been wanting to tell them and giving black people opportunities from the top, not just a figurehead, but all the way down into means of production. I’m also just trying to force a reckoning. I don’t want to have the hubris to think that any one project can transform this country. Clearly, it cannot. But I think we can make certain truths undeniable to a large segment of the population that has not wanted to learn these truths. That’s all I’m trying to do.

PP: That’s it. No biggie. Laughter.

NHJ: Laughter. That’s it—just those two little things.

PP: So to close, what is something you would like everyone reading this and everyone who doesn’t know you very well, what would you like them to know about you?

NHJ: That’s a good question. Damn. I guess I would just say, “If you like me, if you don’t like me, if you agree with my work, if you don’t agree with my work, it’s sincere.” I’m just doing the work that I feel that I’m supposed to do.

Stylist: Lysa Cooper and Rodney E. Hall

Hair: Andrita Renee

Makeup: Ernest Robinson