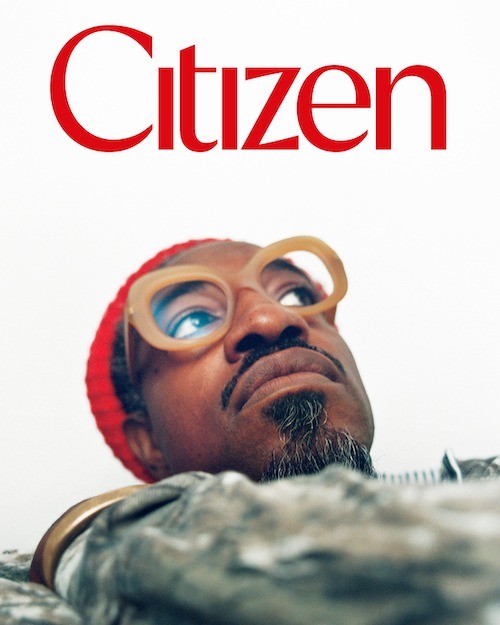

It’s A Feeling. It’s All of Us.

Text by Sarah Osei

Photography by David Nana Opoku Ansah

Issue 002

“Distinguishing between Kendrick and Kendrick Lamar. I’m still learning the balance of that”

Kendrick Lamar is in Accra. He’s there chasing a soccer ball around a cemented pitch in the city’s Jamestown district and for a moment he’s indistinguishable from the other players. Kendrick Lamar is in Accra. By this point, everyone in Accra’s probably seen a text or Tweet like this. The world is watching. Videos on our screens, people milling around the concrete lot looking on, backs pressed against a Tupac mural, it too, watches sagely. It’s the first we’ve seen of K.Dot in years—not counting the Super Bowl or one-off fan sightings. But if I take his word for it, this is not the rap megastar, the icon we all claim to know. Just Kendrick, dreadlocked, smiling, playing in the sun in Ghana, determined to conquer the game.

Three weeks after word spread that Kendrick was among us, he signs on to a Zoom call and I am there to find him again. He is in the form I first met him, in the form in which we all first crowned him the greatest of all time—sound, voice alone. I ask him, “do you prefer audio, or should we do a video?” And he answers calmly as though simply repeating something true, “I’m cool with audio.” He’s alert, he weighs his words carefully and then doles them out with sharp conviction. So, we start with the easy question, easy as in it is what we all want to know: why has he been so quiet for the last five years?

“Distinguishing between Kendrick and Kendrick Lamar. I’m still learning the balance of that. Because I’m so invested in who I am outside of being famous, sometimes that’s all I know,” he pauses mid-thought. “I’ve always been a person that really didn’t dive too headfirst into wanting and needing attention. I mean, we all love attention, but for me, I don’t necessarily adore it. I use it when I want to communicate something,” he explains, “The person that people see now is the person that I’ve always been. For me, the privacy thing has never been an issue that I had to carry out with full intention. It’s just who I am. If I feel I have to remove myself, I just remove myself. I won’t complain about it. I won’t cause a big blow-up or a big stir and let the world know that the walls are closing in. Being able to be aware [of myself emotionally] and be able to eventually grow—emotionally mature to that level, it may take time more than the next man. That’s why I never point fingers when artists are not capable of upholding themselves in that type of stressful capacity because some people grow different and it takes time especially…when who they are and who they want to be sometimes get distorted. For me, it’s all about being aware of how I’m feeling. If it is too much, let me remove myself for a couple of years.”

“I think many people around the world feel this claim to Kendrick Lamar – it goes something like what I’d tell my parents when my high school hip-hop banter didn’t translate: “he’s our Tupac.”“

About five years, to be more specific. But Kendrick’s been watching. Never engaging, just watching. “People ask me, ‘Man, you’ve never been on social media, you really hate it?’ Bro, I don’t really know how to use it like that to be 100% real with you,” he admits with a laugh. “I got friends, family, my team, they send me things, so I got good sentiments on what’s going on.”

For those who have waited in the space between self removal and new release, it felt as though Kendrick Lamar released, DAMN., his fourth studio album, in April of 2017, then floated about scarcely for only as long as it took to complete obligatory promotional commitments, secure a Grammy for Best Rap Album of the Year, and visit Columbia University in New York, to accept the Pulitzer Prize for Music—the first an artist received the award for work outside the genres of classical music and jazz. After this brief period of public life, Kendrick returned to a private one and we waited.

My first conscious encounter with adulation of a rap legend was as a kid, visiting my uncle’s phone shop in the Ghanaian capital, where he mournfully displayed a picture of Tupac – not dissimilar from the one watching over Kendrick in Jamestown. That’s when the trotros (minivans that popularly operate as shared taxis) displaying their love for the deceased rapper like tattoos, alongside Jesus stickers and scripture started to make sense. Then in high school in Kumasi, my hometown five hours inland from Accra, when my proudest thing to wear when I could ditch my school uniform was an oversized Tupac tee. That was around the same time we’d pore over mixtapes at the lunch table and argue about hip-hop like we were the greatest rap critics. And when one name started to dominate our lunchtime debates: Kendrick Lamar.

In time, the words we’d overzealously used as kids – “legend” and “greatest of all time” – came true. We watched the story unfold from afar: a multitalented innovator coming into his greatness. It felt like it was our story. I think many people around the world feel this claim to Kendrick Lamar – it goes something like what I’d tell my parents when my high school hip-hop banter didn’t translate: “he’s our Tupac.”

I think many people around the world feel this claim to Kendrick Lamar – it goes something like what I’d tell my parents when my high school hip-hop banter didn’t translate: “he’s our Tupac.”

About five years, to be more specific. But Kendrick’s been watching. Never engaging, just watching. “People ask me, ‘Man, you’ve never been on social media, you really hate it?’ Bro, I don’t really know how to use it like that to be 100% real with you,” he admits with a laugh. “I got friends, family, my team, they send me things, so I got good sentiments on what’s going on.”

For those who have waited in the space between self removal and new release, it felt as though Kendrick Lamar released, DAMN., his fourth studio album, in April of 2017, then floated about scarcely for only as long as it took to complete obligatory promotional commitments, secure a Grammy for Best Rap Album of the Year, and visit Columbia University in New York, to accept the Pulitzer Prize for Music—the first an artist received the award for work outside the genres of classical music and jazz. After this brief period of public life, Kendrick returned to a private one and we waited.

My first conscious encounter with adulation of a rap legend was as a kid, visiting my uncle’s phone shop in the Ghanaian capital, where he mournfully displayed a picture of Tupac – not dissimilar from the one watching over Kendrick in Jamestown. That’s when the trotros (minivans that popularly operate as shared taxis) displaying their love for the deceased rapper like tattoos, alongside Jesus stickers and scripture started to make sense. Then in high school in Kumasi, my hometown five hours inland from Accra, when my proudest thing to wear when I could ditch my school uniform was an oversized Tupac tee. That was around the same time we’d pore over mixtapes at the lunch table and argue about hip-hop like we were the greatest rap critics. And when one name started to dominate our lunchtime debates: Kendrick Lamar.

In time, the words we’d overzealously used as kids – “legend” and “greatest of all time” – came true. We watched the story unfold from afar: a multitalented innovator coming into his greatness. It felt like it was our story. I think many people around the world feel this claim to Kendrick Lamar – it goes something like what I’d tell my parents when my high school hip-hop banter didn’t translate: “he’s our Tupac.”

“It ain’t how it used to be. But in the ‘90s, it was a family, it was a community. It was us. We were outside every day. Our neighbor was our brother…”

Over the years, since his name first invaded our constant conversation, Kendrick became a vehicle for something greater. A poet, a revolutionary, a prophet. When the world was burning or we had to take a strong hard look at ourselves, he served as our reliable witness. The chosen one who could put our feelings into words. Album after album, he took on this messianic duty, quietly accepting that it was his cross to bear. “You just got to be real and be true to yourself about what you want. Do you want that attention? Do you want that type of notoriety? Do you want that type of headache? Can you deal with it? For me, I knew as an artist when I signed up for it, this is what comes with it. And me being a realist and holding myself accountable to that, it never really frustrated me when these got a little bit out of control because ultimately, I knew that I will be able to balance it because of who I am.” And, when the pressure became too great, Kendrick quietly tucked himself away.

Out of sight but never out of mind. After Kendrick collected the awards bestowed to him for DAMN., we mostly only saw him work. We got glimpses of him on tour, or in song, sparingly lending his voice to other artists and projects. But, no new solo work. Eventually, Kendrick became so scarce that ‘Where’s new music?’ turned into ‘Did Kendrick retire?’

Then suddenly, a period of reflection and preparation came to an end: an album was announced via a blog post, a solitary Instagram image was posted, a song was released, a video was dropped, an album cover was shared. Kendrick, still out of sight, finally had something to say. So what’s he doing, playing soccer at the Tupac mural one moment? Playing FIFA with local kids the next? The whole world is looking for the man, he is reemerging. And, he’s in Jamestown?

It seems as though all we are seeing of Kendrick now, not just the music, is on account of the private space he retreated to. His appearance in Jamestown is too a manifestation of a seed planted in a quiet place. “These are ideas we had back two years ago,” Kendrick says. He recalls that an associate, Sabine Le Marchand, first turned his years-long desire of returning to Africa into an idea to visit Ghana. “It was really pivotal for me, especially at this time of my life where I’m evolving,” he declares. “This trip was very pivotal for me in that moment of saying, ‘Okay, let’s take the time out of moving and hitting the ground so hard…[Let’s] feel something a little bit different from what we understand or what we’re accustomed to in the States.’ In this process of me finding a new sense of self, Ghana was home for that.”

Kendrick has been meaning to make the journey since 2014 when he first stepped onto the continent on a tour to South Africa. “That was the first time I experienced a show [where] I don’t think the intensity ever dropped, not on one song. Not even on the interludes or the down-beat songs. We was doing records that was super mid-tempo but you look at the crowd and the people was enjoying themselves. We was moving at 134 BPM and the type of love, the freedom of expression, and just the love for sound, it was different. This is what we do. This is our DNA, to be expressive like that and to enjoy that. This is completely different from anywhere else because this is who we are. We create music. We love music. The feeling was different.” Africa left its mark and the urge to return was almost immediate. “When we all got on the plane going back to LA from South Africa, nobody wanted to leave. It was like, ‘Man, you feel something? You feel weird?’ I’m like ‘Yeah. You kind of don’t want to leave. I want to stay for a little bit longer.’”

The energy of performing in Africa for the first time was something spiritual and it famously catalyzed his next album To Pimp a Butterfly. If South Africa was the blueprint, perhaps Ghana could be his way of replicating the butterfly effect? But Kendrick wasn’t looking at things that way. While in Ghana, his deeply insightful double album, Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers dropped, ending a five-year hiatus. South Africa may have lit a flame for the curious artist, but in Ghana, he emerged from a profound magnum opus and granted himself some respite.

“The Ghana trip was even more intense. Because this time I wasn’t just performing. I was actually in the mix with the people. So knowing the difference, we felt like our spirit was more alive,” he tells me. “Coming back [to LA] was like, ‘how can we take this same spirit and put it with our everyday lives to where it makes sense?’” That recognition, the need to reflect back, is an essential aspect of where he is now in his journey.

Kendrick isn’t occupied with being the sage, unerring rapper we all want him to be – “The cat is out the bag, I am not your savior,” he proclaims on track 5 of The Big Steppers. “My ego is alive and well,” he tells me. “That bravado comes out in my music every now and then just from a skill basis and me being a student of the culture, of what rap thrived on and that was competition […] When I see the accolades, it’s beautiful, I love that but there’s also awareness in knowing when I need to use it, that part of the ego, and when I need to put it up. And I think this album in particular is a more personal album for me. This is me stripping away my ego. On my last album, my ego was there. You’ll hear it on records like “HUMBLE.”, you hear a lot of bravado on “ELEMENT.”. But this is taking the cape completely off and saying it’s okay to replace the ego with vulnerability.”

Hip-hop usually doesn’t give its practitioners the longevity to evolve to the point where they can step off the pedestal and appraise themselves in this way. Only the greats are bestowed this privilege. “The same way Nas, Jay, Big, Pac, laid the blueprint for me, some of the text messages that I have in my phone about records like “Mother I Sober,” “Father Time,” and “Aunty Diaries,” some of these things these guys are telling me and expressing to me, it’s overwhelming, and it’s beautiful because it shows me the evolution of where hip-hop is going and how far it will go even after me, when I want to fade in the shadows,” says Kendrick.

And that’s the way it is with Kendrick; after presenting a disarming body of work, it’s as likely that he’ll disappear again for half a decade as it is that you’ll find him strolling through the streets of Accra with a milling crowd of onlookers. He’s eager to know this new place that vaguely feels like home. On a quest for “pure inspiration,” which Ghana eagerly answers.

“What I got out of the trip was there’s still individuals that have a heart with no intentions. When you’re in this business, man, you have some really good people, you have people that have evolved to not knowing love because they’ve become so desensitized to hurt or getting over on people or having a straightforward outlook on what money does for them in the grand scheme of things.” He ponders on how easy it is to get lost in the industry. But, “the simple things in life still matter. To see a man waking up in the morning and he’s saying, ‘My only intention today is to go out and bring back fish for my family. That is my goal for today.’

That shit is mind-blowing to a person that has several things to do when they wake up—and they can’t even get one thing done because they’re so focused on doing multiple things at one time.” Kendrick is pulled back to core intentions and what it looks like to be driven by purpose rather than process. There’s a profound similitude when we strip life back to its essence. Suddenly the proud survival of a Ghanaian fisherman isn’t so far removed from an international superstar’s own hard-knocks upbringing in Compton. He remembers himself.

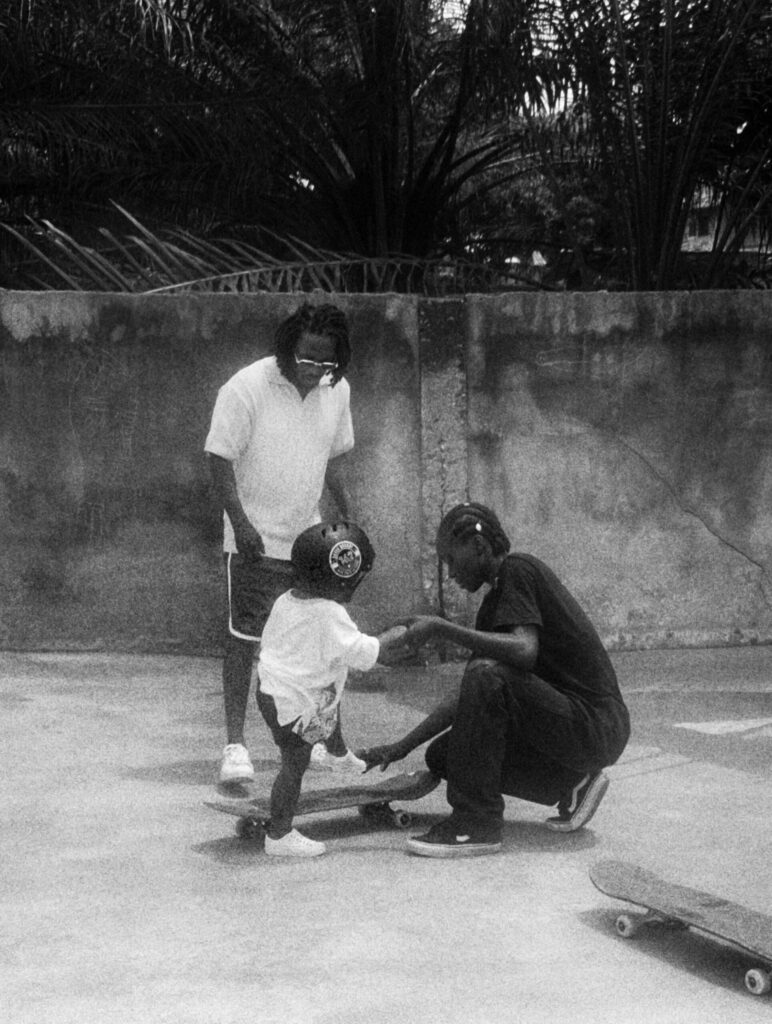

“That made me think of the ’90s,” he begins to reminisce. “It ain’t how it used to be. But in the ’90s, it was a family, it was a community. It was us. We were outside every day. There was no internet, there was no Instagram, there was no Twitter. We were outside. Our neighbor was our brother, we fought with these dudes. A lot of people don’t know that gang culture is derived from brotherhood and fellowship, the same dudes that we fought with, we grew up with. So it’s a personal type of love, a different type of love where you can fist-fight your brother next door and then hug them at the same time. That’s what I saw when I went to Jamestown. Everyone’s family. These people came up together and they hurt together, they bleed together, but they love one another, and that’s what I’ve seen in Compton, being a child in the 90s, born in ’87, and watching my uncle’s fellowship, their friends and our aunties. We spent nights at each other’s houses and learned from our mistakes. Going out, figuring out how to bring back food to our families. It was just something that I felt before. In order to feel that again, I had to go outside of myself and go outside of my own community to see that.”

Accra has become the beating heart of a specific kind of African renaissance, combining a thriving creative youth with a concise policy effort to welcome back black diasporans. And many superstars – from Muhammad Ali to Beyoncé – have made the pilgrimage. So it’s not the wildest thing that Accrans now have Kendrick Lamar anecdotes under their belt too. But Kendrick didn’t follow the usual PR script. Even without the engineered meet-and-greets and tentative collaborations, on the ground, his encounters with Ghanaians revealed a deep appreciation for his craft and his journey so far – as if to say, We’ve been rooting for you. We believed in you from the very beginning.

“People would tell me, ‘you have a huge following and you have a huge impact in Ghana,’ but that only goes as far as them telling you. I had to go there and experience it. I’ve been hearing it for years, but I don’t know, until I’m in the city, I’m talking to people, I’m seeing the smiles on their faces, they asking me questions that I haven’t heard since my first mixtape, holding up T- shirts of my old mixtapes, that’s what I needed to feel. It’s only so far that words can take me to explain the impact that was in Ghana.” He speaks of the energy he received with awe. He’s not usually this comfortable in crowds, they can be overbearing, but this was different. “You can feel the level of pure love and respect,” he explains. “And when you feel that, you don’t mind taking 1,000 pictures…It’s a freeing feeling for me as well. They may feel like they’re getting something [out of it] and getting their spirits lifted, but it was vice versa, there was a mutual feeling.”

“Now, I’m dropping the ego a bit. I want to take ‘the greatest’ off of [‘greatest of all time’]. I want to give people something they can hold onto. So whether it touches 100 million people or inspires one, I want to be that person.”

There was one commercial stop on his trip, however. A “private” album release party held by Spotify felt like more of a formality. The who’s who of Accra piled into the Rehab Beach Club, stretching the guestlist and open bar to its limits. Kendrick showed up with his entourage, greeted a few Ghanaian artists, and left again. The event easily became fodder for overnight critics, some artists allegedly felt slighted, and some fans protested the elitism of such an event. Kendrick Lamar quietly left the country, without saying a word.

“My focus primarily was for self,” he calmly tells me. “It had nothing to do with music. And that’s no disrespect to all the artists that are out there. I met a few crazy artists that I had to go back and do my research on when we did the Spotify event. But yeah, the intention was really to isolate myself. I didn’t want to think about music too much […] Maybe the next go around, my full intention will be to get up with the people that I’ve learned to study and listen to.”

Without the urgency to bunker down in the studio, musically Kendrick approached Accra as a curious listener. He took in the sounds of the highlife capital, from fans chanting forgotten lyrics back at him to going to speakeasies hearing old underground records mixed in with new music. “Where the city is at as far as culture and sound and blending in, it made total sense to me, that their ears are connected the same way we trying to be connected.”

But even with his intentions far away from work, the sounds of the city awakened the artist. He describes nights out in Accra, the exhilaration of hearing new songs. “I just kept nudging on, leaning over to [my folks] like, ‘What is this? Who is this?’ And one thing that captured me was the drum brakes that I felt had a little bit more of an intricate detail route. I study sound and I really like to listen to patterns. We have patterns. We come from the root of the drum, being that we all from Africa. But it was something that was a little bit more intricate and pulsating with drum patterns versus the 808s and it resonated in my spirit.” He admits that ever since he left Ghana, he’s been trying to replicate those drum breaks and how they made him feel.

“It’s authentic. You cannot fake being authentic. What we seeing from [African artists] is just the heart and the nature of creativity, without being bound by first-week sales, last-week sales, what sound you got to do to get on top of the playlist. We just feeling something rather than seeing a number. I think that’s what they bring to the game and it’s exciting. So you see a lot of the global artists wanting to learn and express themselves the way that they’re doing out there. And it’s a beautiful thing to see, to merge them type of genres. I mean, it’s all black at the end of the day. It’s all us, it’s all grassrooted. But now we have to fully embrace it because it’s coming, whether the industry likes it or not. It’s a feeling.”

For those on the continent, the question is no longer whether Africa is the source, but when Africa will be able to take part in its own legacy. On his part, Kendrick hopes to set the precedent for other Black performers coming from abroad. Another Africa tour “has to be done, I encourage more artists to do it,” he insists. Africa is no longer the strange, faraway place he saw on infomercials as a kid, it’s also not something to keep on the constant back-burner – “It’s our home.”

“My intention is to not make it a one-year trip. But to go back multiple times throughout the year, whether it’s for music, for culture, for learning, or whether it’s for self. I can’t afford to hold it off like I’ve done for years. I got children now. I want them to see things that I wasn’t privy to and be able to experience things outside of what they know.”

Kendrick is giving himself the same grace to expand his creative world, too. Going beyond music to push the boundaries of creativity. pgLang is his playground, the mysterious media company he launched with his longtime creative partner Dave Free last year, cryptically suggesting a new all-encompassing creative chapter on the horizon. “When [Dave and I] first sat down, we said we wanted to do something for creatives. We see where the industry is going and we’ve dealt with the politics and learned the ins and outs, man, we’re still learning to navigate our own thing. So initially, it was to make that sub-system for people that just want to create, the same way Virgil inspired kids, it’s a collective of us that still want to do that…show that there are still artist-friendly imprints that uphold the integrity of the culture. That’s what we’re striving for.”

“Creativity is everything,” he professes. “I think creativity is that outlet for good, for people to be able to evolve. We live in a world and society today where everything is crippled and the low vibrations of people, in general, is stagnant. So creativity is our outlet. And as long as I’m here to strive to push that envelope, I’m going to find other individuals that want to carry on the same tradition.”

Kendrick’s foray into agency work represents something both old and new. It is old in that the artist’s creativity is rooted in a legacy much bigger than the self, always for the people, reaching out beyond sound, spilling over. What is new is the intentional change of mediums the art— morphing from one form to the next like the series of deep fakes in his “The Heart Part 5” video. What’s new is the ownership of one’s “brand”, the tight control of the artist’s output within and beyond music, simultaneously in response to and in rejection of the digital age, and the legacy of an industry that has benefited from all parts of the artist while cutting the artist out of the beneficial parts. He represents the new music artist that sees beyond the present moment.

“My initial goal as a 13-year-old boy was to be the greatest rapper, from the time I got in the studio with my guy Dave Free and his brother Dion, and they set that microphone up. That was my initial goal and that goal went from being a great rapper, the greatest rapper in my community, Compton, then I wanted to push my pen to be one of the greatest rappers outside of the city. And that itself started to evolve to ‘I want to be one of the greatest artists. I want to be one of the greatest poets.’ Now, I’m dropping the ego a bit. I want to take ‘the greatest’ off of it. I want to give people something they can hold onto. So whether it touches 100 million people or inspires one, I want to be that person.”

Kendrick Lamar has millions of us in his palm. But he’s right, it only takes that one person, that one encounter to impact a life. Like when an eight-year-old Kenny met his idol Tupac on the set of a music video in Compton. Maybe, that day their favorite rapper materialized in their neighborhood, one of Accra’s bright-eyed kids stared up at their own destiny too.

“I know what my forefathers have done for me. So I’m waiting to see where it goes. But for right now, I’m going to continue to push the envelope for the next however-many years. It will be a complicated but fun ride for the greater good of the listening ear and the greater good of humanity.”

Credits

Photography: David Nana Opoku Ansah

Words: Sarah Osei

Stylist Assistant: Emmanuel Affedzie

Makeup: Abby Boat

Hair: Asia Clarke

Photo Assistants: Julius Tornyi, Tony Bright

Set Design: James Avaala

Gaffer: Ibrahim Yakubu

Art Direction/Design: Othelo Gervacio/ Jordi Ng

Production: Ekow Barnes/WB Group

Post-Production: INK