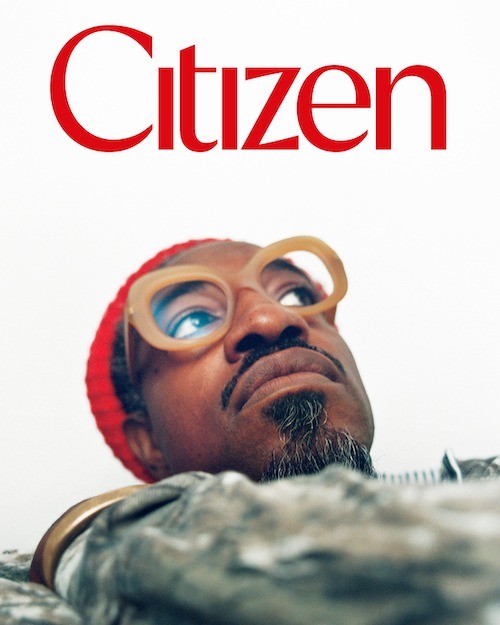

Only One, Tina Bell

Only One, Tina Bell

Oscar-winning filmmaker, T.J. Martin, recalls searching for evidence of his mother’s full and known existence beyond the conjecture, beyond the designation: Tina Bell, Queen of Grunge

Text by T.J. Martin

Images Courtesy of T.J. Martin, Scott Ledgerwood, David Ledgerwood & Cydia Lavik Michelle

Issue 002

In 2012, my mother wore a hat to hide her thinning hair. She no longer had a favorite outfit. She listened to Metallica. The Doors. Frank Sinatra. She was Black, she was beautiful, and when someone questioned her drinking habits, she would smile and tell them to mind their own business.

~

My mother was found dead in Las Vegas in the Fall of 2012, in the studio apartment where she lived alone, a few minutes from downtown and the old strip. Her body was frail, her mind had been agitated. She hadn’t worked in more than 20 years. She had withdrawn, almost entirely, from the world. She was 55 years old when she died and following her death there was silence, no reporters, no memorials with teary-eyed people recounting specific moments in her career. Her name was Tina Bell. She was the front-woman for the 1980s rock band, Bam Bam.

Tina Bell is not a household name. But maybe in some parallel universe, she could have been. Before she withdrew into alcohol, seclusion, and depression, my mother had been the frontwoman of a Seattle rock band called Bam Bam. My father, Tommy Martin, was the founding member and lead guitarist. Bam Bam was a fixture of the Seattle music scene in the mid-80s, just before that rain-drenched, blue-collar city went unexpectedly global with a sound that would come to be known as “grunge.” Bam Bam’s first drummer was Matt Cameron who would go on to play in Soundgarden and Pearl Jam. A young Kurt Cobain was a fan and sometimes roadied for the band. Bam Bam recorded their one and only EP, Villains (Also Wear White) at the same studio where Nirvana would record their debut album Bleach just a few years later. But by 1990, Bam Bam, my parent’s marriage, and my mother as I knew her would all fall apart.

“I asked about her belongings and the manager gave me a laminate poster of family photos, a DVD player she used to play CDs, and a broken wooden chair.”

The story of what happened to Bam Bam and what happened to my mother is the story of my childhood. The band and I were conceived almost simultaneously. Just a few years before she died, my mother told me a story she’d never shared before. It was 1979 and she and my father had recently met and fallen in love. My father was starting a band and wanted my mother to be the singer—but he insisted that she audition for him. One night while lying in bed, she sang Dionne Warwick’s “I’ll Never Love This Way Again” and that was it, my father fell even deeper in love and declared that this band would be the two of theirs, together. Tina Bell and Tommy Martin. Bell And Martin. Bam Bam. What she didn’t tell my father at that moment was that she was pregnant and had sung the song to me, the child she didn’t know yet, devoted to the love she already felt for me. When she told me this story, I was speechless for a moment. My mother was not one to share sentimental stories and as I started to tell her what this meant to me she quickly interjected to say, “But don’t tell your father, he still thinks I was singing about him,” and let out her signature cackle.

When I received the call about her passing I was shocked but not surprised. The years leading up to her death were a filled mystery even to her. She shared with me on a couple of occasions of being overwhelmed by the voices in her head and the subsequent physical pain it caused. Her mind, her body, and her world were unraveling.

Forty-eight hours after the call, I arrived in Las Vegas to retrieve my mother’s affairs. There was still police tape on her door. I met with the building manager and learned that a stench had been coming from the apartment for several days before the police were finally called. I was told they knocked down the door to find my mother decomposing into the carpet. According to the coroner she had been there for 2 to 3 weeks. She had died of cirrhosis of the liver. Her alcoholism eventually caught up with her. I asked about her belongings and the manager gave me a laminated poster of family photos, a DVD player she used to play CDs, and a broken wooden chair. They were presented to me as though they had been saved from a fire. What about her writings, her poetry, her journals? What about her demo tapes and home recordings? I was told that everything else was gone, thrown out because of the “contamination” in the apartment. I was confused, angry, and at a loss. The carelessness exhibited by her landlords would not only create emotional turmoil for years to come but would also put her legacy in jeopardy.

Since my mother’s death, Bam Bam’s first bassist Scott Ledgerwood has been tireless in his efforts to bring awareness to my mother’s impact on Seattle music. With the copious articles, books, and content exploring the story of Seattle and the “grunge movement,” I’ve only been able to find one sentence about Bam Bam. And even then, the author’s mention of the band claims it was a three-piece instrumental, erasing my mother from history.

Scott’s relentless efforts eventually got the attention of a few international publications, run by women of color, astonished by the mere idea that there was a Black woman in Seattle fronting a proto-grunge band. And even more, taken aback by the erasure of her contributions to a then nascent scene. The accolades and recognition began to draw the attention of major news networks and various national newspapers, eventually leading to her being coined the “Queen of Grunge.” In my eyes, my mother is certainly a Queen but even she would laugh at such a title.

Late in the Summer of 2021, I was contacted by a curator from the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. She was interested in featuring my mother’s story in their permanent collection for Music and Performing Arts. I was stunned and honored by their interest in her. That my mother’s work as a singer and songwriter mattered to people. That even the tragic way her ambitions were cut short was of value. I began to imagine this future exhibit and was immediately gripped with uncertainty. Traditionally museums are spaces that use artifacts as a means of giving insight into someone’s narrative and here I was with nothing to show of her work. What items could I contribute that would ultimately define and shape her story? A story that even I knew very little about. One shrouded in mystery. I found myself in a panic reaching out to friends, family, and colleagues in search of any memorabilia that would help give a window into her work and her identity.

“I felt a wave of what the Portuguese call saudade. A painful kind of joy, a joyful kind of pain.”

In 1979 my mother wore her hair short. It was relaxed and always freshly oiled. Her favorite wardrobe was a loose flower print summer dress to let her pregnant belly breathe. She listened to Billy Holiday. Nina Simone. Dick Haymes. She was Black, she was beautiful and if you asked her opinion of her calling in life, she would say to be in service of others.

~

My mother was born and raised in Seattle along with 9 brothers and sisters. Her mother had come there as a child from Louisiana during the Great Migration. My grandmother was the only Black student in her class and when she saw her class photo, she used a marker to blot out her face. As she explained to me, she felt intimated, insecure, and alone. This was a foreign place and this is how she coped. Some years later, in an act of defiance and independence, she would mark her classmates’ faces but leave her own untouched. My mother may have channeled that defiant, independent streak when she chose to be the frontwoman of a Seattle punk rock band.

She grew up singing at the Mt. Zion Baptist Church in the historic Central District. She was drawn to choir and drama. As a teenager, she landed a starring role in a play at the Langston Hughes Performing Arts Institute and was going to sing Eartha Kitt’s rendition of “C’est Si Bon.” Because she didn’t speak French, my grandparents hired a tutor through a local ad. A handsome young white man named Tommy answered the call.

My father was the son of a scientist and a stay-at-home mom, the third of four children, and the self-described “black sheep” of the family. He had played guitar from the age of seven and carried it around with him like another appendage. Tina and Tommy fell for each other fast and they bonded quickly over music and a passion they both shared for creative expression. They both felt they had something to say to the world —and they wanted to say it loud.

In the Fall of 2019, my father was found dead in Seattle, Washington. He had been living in a trailer parked on commercial property where he was building a music studio. He still had dreams of making a name for himself as a recording engineer. After Bam Bam dissolved, my father didn’t hide away as my mother did. But he was in another kind of stasis, unable to move on from what could have been. Like my mother, he self-medicated. After his death, the toxicology report showed traces of cocaine and fentanyl in his system. The coroner ruled his death an overdose. He too was found alone. He was sixty years old.

Forty-eight hours after I got the call of his death I found myself, again, handling the remnants of a parent’s life. When I walked into his still-unfinished studio, it was like walking into a hybrid recording studio, Salvation Army, and man-cave. His hoarding tendencies seemed to increase with age. Amidst the Shure mics, Boss pedals, Soldano amps, band stickers, and backstage passes, I found a cassette tape with a handwritten label: “Tommy and Tina – a couple and their music.” It hit me in the gut. Here among the detritus of my father’s life was this relic of their past, of my past. I had never seen nor heard of this tape. I brought it with me back to Los Angeles where a friend digitized it for me. When we played it back, the crinkly recording hissed for a few seconds before a familiar guitar riff and a loud scream burst through the speakers. This was my mother and father laying down an early demo of the title song of their future EP and the song of theirs I loved the most growing up; Villains (Also wear white).

Bad guy portrayed in black

Show another side

Victim of some rude act

Got no place to hide

Villains also wear white

Villains also wear white!

Then, in the background, I hear a baby crying and the song is cut short. I felt a wave of what the Portuguese call saudade. A painful kind of joy, a joyful kind of pain. There we all were—me, my mother, my father, and Bam Bam. These bittersweet sounds of the early days—an echo of the past and the promise of what could have been. When we were still a family. When two young musicians, full of creative passion, still believed they were going to take the world by storm.

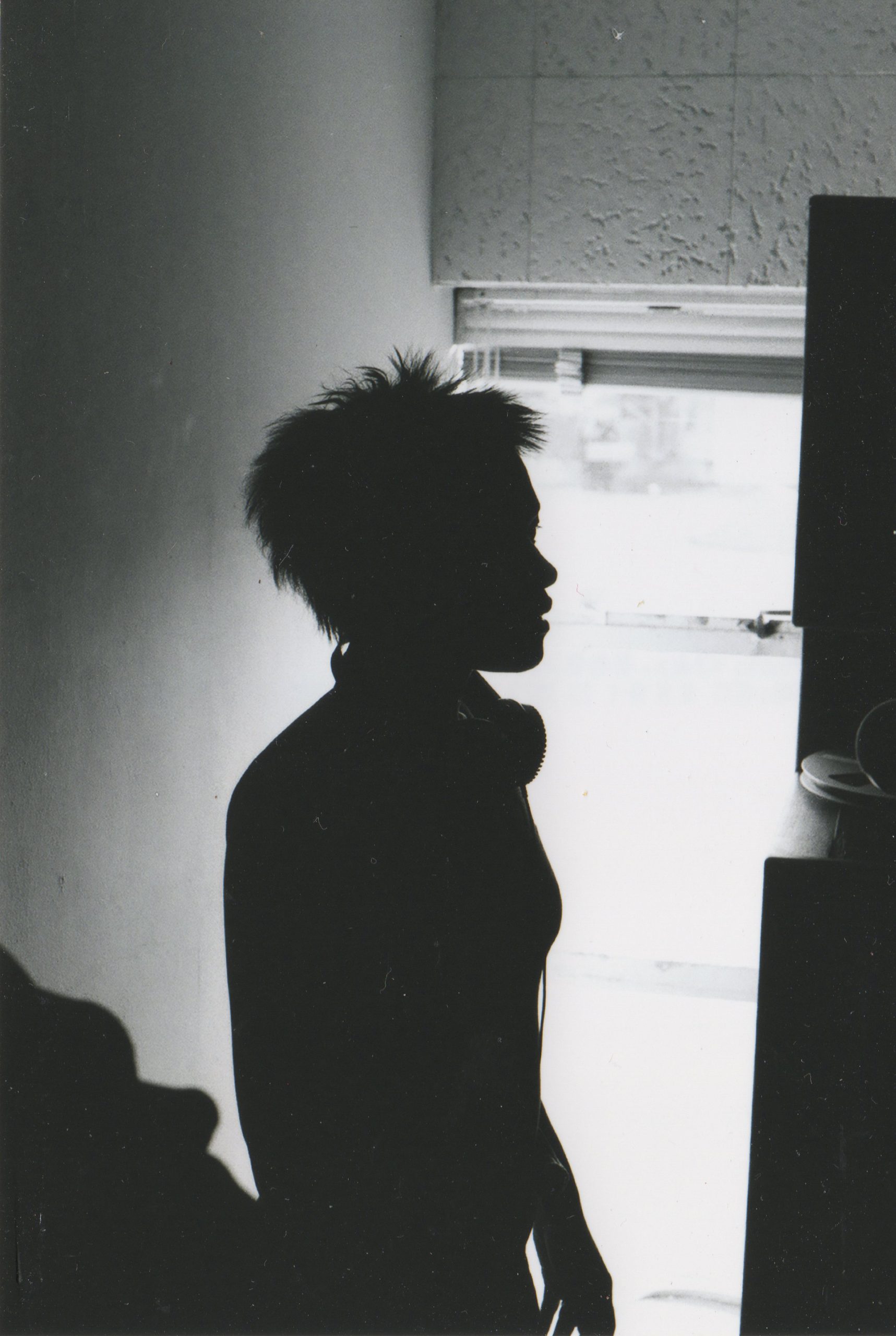

In 1984 my mother wore her hair natural. She would comb it out ever so slightly creating small feathery spikes. Her favorite wardrobe item was her members-only jacket. She listened to The Pretenders. X. Bad Brains. She was Black, she was beautiful and if someone told her that cigarettes were bad for a singer’s voice, she would light one up and blow smoke in their face.

~

My father was the band, my mother was the creative engine. Her lyrics and her voice were at the core of Bam Bam’s sound. Although drummer Matt Cameron wasn’t in the band for long, my mother made an impression. Recently, on the podcast Seattle Today, he reflected, “Tina was phenomenal…I’ve worked with some of the greatest singers of my generation and she’s right up there… charisma, power, her lyrics were fucking cool…She was one of the greats!” My mother stood at five feet two inches but on stage, she had the presence of Mike Tyson.

In 1984, they recorded their debut EP, Villains (Also Wear White) at the newly constructed Reciprocal recording studio, which would later become a staple in the Seattle scene recording bands like Nirvana, Soundgarden, and Mudhoney. From all accounts, Bam Bam was the first band to officially record with Reciprocal. But that first was also a last–it was the last professional recording of my mother on vocals with the band.

Listening to the record now, I find myself paying more attention to her lyrical prowess, conjuring new ideas about her life that I have never considered.

Been stripped of my keys.

I ain’t got no job.

Back at the crib the baby’s cryin’.

I live for Benny Hill, when it’s time to go to bed.

I’ll be fine until it’s time to wake up again.

Two in the morning; my body shakes from head to toe,

Upstairs the toilet runs over..

Still baby’s cryin’…

The telephone rings with bill songs.

The mailbox brims with; you’re overdrawn…

Your account is overdrawn!!

I burnt the beans. The minute rice is under cooked.

Now daddy’s cryin’.

I live for Benny Hill, when it’s time to go to bed.

I’ll be fine until it’s time to wake up again.

In these lyrics, I hear Tina the singer, Tina the artist, and Tina my mother wrapped in between each word. It is a part of the fabric of my life, my mother’s voice travels through the years bringing with it flashes of our family life–touring and sleeping in vans, waiting in line at the food bank, depending on food stamps–and the lives they lived outside of my view—cocktail waitress, weed dealer, bus driver, cashier, hairdresser, janitor, and dancer.

But, like a landscape illuminated by brief flashes of lightning, I only get glimpses. I cannot see the full picture. I hear my mother on these recordings, I see pictures and grainy video from their live performances but I can’t connect that presence with the woman she became, withered and withdrawn.

In 1986 she wore her hair in thin short braids and dyed them white. Her favorite wardrobe item was her black leather jacket. She listened to Peter Gabrielle. Aretha Franklin. Sister Rosetta Tharpe. She was Black, she was beautiful and if you asked her what her favorite color was, with pride she would exclaim purple!

~

By 1986, the scene in Seattle was feeling by turns stagnant, hostile, or uninterested. Although Bam Bam had garnered a following in Seattle, they—and specifically my mother—were not always welcomed. My father and others have told me stories from their shows, of young punks and skinheads hurling racial epithets at my mother. They told me of at least one instance where my mother responded by swinging her mic stand and smashing a couple of offenders in the face. On that occasion, my father jumped into the fray, guitar still slung over his back, ready to use his black belt in karate to defend my mother. There’s an absurdity to these stories, a carnival quality not unfamiliar to grimy dive bars where punk bands play. But this wasn’t punk mayhem, this was the blight of racism. For some audiences in Seattle, a Black woman fronting a punk band instead of a Soul or R&B act couldn’t be serious. The Tina Turner references grew old, and the white, fraternal nature of the music community and occasional sexist and racist acts began to take a toll on my mother.

Around the time of my mother’s memorial, my grandmother handed me a photocopy of a letter she had written to her while on tour.

April, 15 1986

I hope that this letter finds everyone in the very best of health and that all is going well….So far, we’ve been to San Francisco where we did two shows with the band. Both shows went over very well with the crowd. One (at this place called “The Farm”) was almost ruined for me because of this little “punk” boy that tried to spit on me while I was singing. I stopped singing, kicked him in the face as hard as I could, picked up the mic stand to clobber him good when the producers of the show ran on stage to stop me. I didn’t know that spitting was the “punk” thing to do and It’s not really meant as an insult. It told him off over the microphone anyway. It was great!!!

Little did that “punk boy” realize the trauma she had endured her entire career and how close he came to being another victim of my mother’s “no bullshit” policy on disrespect. It’s hard to imagine how lonely her island must have felt, dodging racist slurs, men aggressively hitting on her, and navigating female peers who felt her “Blackness” was an act for attention.

It is not surprising that my parents followed in the footsteps of other Black American artists. They looked to Europe as a place where they might find more open-minded audiences.

~

We lived in Europe for two years. My parents split their time between Amsterdam and London and sent me to boarding school in the Southern part of France. I was seven years old, was only armed with the most basic words, like “oui” and “non” and “merci”, and had never been outside of the United States. It was hard for me to make sense of what felt like a form of abandonment. When I ask, no one can quite recall the story of what happened to my parents during this time. I only have partial anecdotes involving infidelity, squat houses, and very little music being made. What I do know is that visits to the boarding school where I had been placed became increasingly infrequent and almost wholly independent of each other. Their fights grew more violent and their relationship ultimately fell apart.

“I’m proud that she is getting this long-overdue public recognition but the impression and feeling she left on those closest to her is what I carry with me.”

In 1990 my mother’s hair was teased out and bleach white. Her favorite wardrobe item were her black 85’ Nike Dunks. She listened to Eartha Kit. Alice in Chains. Napalm Beach. She was Black, she was beautiful and when someone would ask her about her whether her hair was real or a weave she would tell them to mind their own fucking business.

~

We returned to Seattle. My parents wisely decided to get a divorce. They unwisely decided to stay in Bam Bam together. At Reciprocal, where they’d recorded their EP, Nirvana, Soundgarden, and Mudhoney had all made their debut recordings. The Seattle sound, of which they had been part, was crystallizing. It was at this moment, when “grunge” was becoming something definite and known, that my parents’ marriage, my parents’ band, and my mother’s sense of her place in the world were all coming apart into little unknowable pieces.

When we spoke about it years later, my father told me that he believed that the racism, the misogyny, and the lack of respect and recognition began to take a toll on my mother. Her tolerance for collaborating with my father diminished substantially. Her creative output plummeted, her drinking increased and she began to retreat. In 1990, Bam Bam was heading to Portland to record a follow-up to their Villains record. On the day they were due to depart, my mother simply said, “I’m not going.” My mother never played music again.

At my mother’s memorial I invoked one of my favorite quotes, from Maya Angelou: “I’ve learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.”

With both of my parents gone, the story of Tina Bell and Bam Bam is simply that, a story. A story that was once obscure and special. One that only a handful of people knew and celebrated. Our cultural obsession with the extraordinary has seemed to give greater meaning to my mother and the life she lived. Yet the pursuit of any artifacts to prove her existence has only revealed more mysteries. I find myself chasing evidence of her musical influence so that others can find meaning in her narrative and as a result, I’ve lost sight that my mother has been extraordinary to me all along. After meeting with numerous friends, family members, former lovers, and collaborators, they all shared that similar sentiment. Her kindness, creativity, humor, and affection for her community in the face of her demons is what made her extraordinary. I’m proud that she is getting this long-overdue public recognition but the impression and feeling she left on those closest to her is what I carry with me. If the rest of the world needs to define her legacy as the “Queen of Grunge” then they’re the ones missing out on the opportunity to celebrate a woman who’s depth was immeasurable–incapable of being codified in catchy headlines. To do this is to make her life over in service to the moment, rather than one that exists across time and place.