Sheila Atim is Falling In Love

Text by Taye Selasi

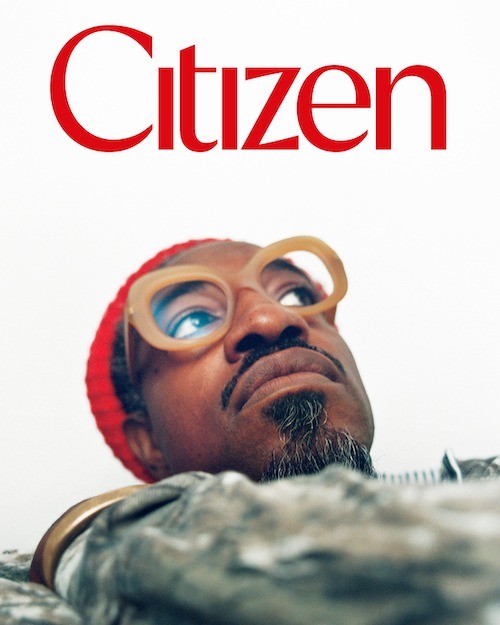

Photography by Tino Chiwariro

Issue 001

Born of a new generation of African immigrant artists with big brains and bigger hearts.

Sheila Atim is a shapeshifter.

When I meet her, first, in the opening moments of Barry Jenkins’ Amazon series—that masterful adaptation of Colson Whitehead’s THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD—she is heroic. Nearly six feet (182 meters) tall, all dazzling cheekbones and defiant shoulders, Sheila Atim is a warrior goddess. Heroine par excellence. But when I see her next, in a video clip of her star-making scene in the British play “Girl from the North Country,” singing Bob Dylan, Sheila Atim is heartbreaking. The bone structure is, of course, unchanged but the being has transformed: From wildness to wistfulness, vulnerability. Not power, but pain, embodied. Eyes closed, she sings with the vocal control of a chart-topping songstress—pairing, improbably, the heart of Adele with the hurt of Tracy Chapman.

I shouldn’t be so surprised, perhaps. This is what actors do. They transform themselves, again and again, shedding and growing new skins. And still, I think. Certain skins are harder to shed than others. For a girl born in Uganda in 1991, shuttled to England in search of asylum, raised in a mostly-white working class suburb: Skin is no neutral phenomenon. To be seen, as a black woman, for one’s nuanced humanity; to demand, as a black actor, a contemplation of humanness; and to do this, simultaneously, in the English and American entertainment industries—This is a feat. Even before I meet her, I know: Sheila Atim is a force.

And so I am shocked, plainly, when she appears on screen for our midday Zoom conversation. Propped on her couch in a cozy turtleneck, eyes twinkling with curiosity, Sheila Atim is, now, sweetness incarnate. Though her publicist has granted only one hour, Atim gifts me three, speaking with transparency, intelligence and wit about her life and her work. There is something so shockingly balanced about this enthusiastic young woman (so young!), a 30-year-old whose boundless talent and curiosity have, together, launched her to stardom. It is rare, I think, to find an actor who can find the hero and the heartbreak within herself—while remaining IRL (as her generation might put it) both pragmatic and playful. That is to say, for all of her success, Sheila Atim isn’t fussed. She’s girl-next-door grounded.

And funny. Laughing all the while, we speak about her best friend from secondary school, the British-Nigerian DJ Juba (aka Chinwe Pamela Nnajiuba); about her experiences working with black Hollywood royalty like Barry Jenkins and Halle Berry; about her mentor, the Camden-born acting coach who taught Michaela Cole and Daniel Kaluuya too; about her forthcoming trip to Uganda, the first in over a decade. It feels as if I’m speaking with a brilliant younger cousin: Born of a new generation of African immigrant-artists with big brains and bigger hearts. What’s clear at the end of three hours is this: Sheila Atim is a star.

“I’m falling in love with myself. There you go. I’ll say that. I’m finding out how to fall in love with myself.”

On coming from—and going back to—Uganda

No one’s ever asked me that question. I think it’s because I was only there for five months, so people maybe deem that part of my life to be less relevant than it is. Of course it’s relevant.

You’re growing up with a parent who has an accent: That’s the bare minimum, even if we never talked about. There’s that cultural negotiation, between being from Essex, England but also having this other culture, and actually really enjoying that—enjoying the fact that you’ve got all these different sides that you can access.

Obviously, I was five months when I left [Uganda] so I don’t remember much. But, recently, my mum’s been telling me a bit more about that story. She talked about it a lot when I was a kid, but they were kind of weirdly fun stories—stories that she managed to put some levity into—so I didn’t fully grasp the concept of war. I think it’s only when you’re older—when you understand time as a concept, when you understand consequence and lineage and heritage, when you understand generational connections—that you can really understand.

When I did the show “Les Blancs” at the National Theatre, a lot of realisations started rushing towards me. [The play] is set in a fictional African country on the brink of civil war, about somebody who’s from there, who’s moved to Europe, who’s coming back, and who has to decide whether to get involved in this war. For a lot of us—particularly the younger cast members, first generation living in the UK—it was a real reckoning with where we come from. As I’ve got older I’ve been really feeling the pull to become fluent in Acholi. I actually have an online lesson later today. I was looking and looking and looking—like: There’s got to be someone on the whole of Google that can teach me this language!

I started writing a project, a script sort of exploring these topics, in the middle of [the 2020] lockdown. But I kind of hit a wall, because I haven’t been to Uganda in 12 years. I haven’t been to the north since I was born—or ever in fact; I was born in Kampala. And over the last eight years, things have been really busy; being an actor is just so sporadic and unpredictable. It feels crazy that at 30, I haven’t been able to go back home yet. This [project] kind of prompted the realization that I needed to go very, very soon.

“I understood that although I had a similar experience growing up as a lot of my White working-class friends did, they have a generational lineage here that I don’t have. And so, if I fail, if my mom fails, that’s it.”

On the magic of a low-cost music class

Because I was an only child, I got very good at entertaining myself by way of drawing things, painting, making things up. And I was a musical child. We had three introductory recorder lessons [after which] the teachers said, “You can learn any instrument you want.” I wanted to learn the flute initially, but the flute teacher wasn’t available until the next year. So I learned violin. I just wanted to do whatever was available. There was a wonderful piano teacher in my area in Essex called Helen Gowlett; she did classes for £4. It really helped that I’d learned to read music by way of the recorder. It’s a real testament to the state schools that do make the effort to create these artistic opportunities. When you’re young, even though you know you like something, it might not necessarily be something that you’d ask for; you’re not thinking that far ahead. So presenting opportunity to young people is really important because sometimes they don’t even know that they want or need the opportunity in the first place.

On the path from science to singing

Interestingly, it was less of a shift and more of a sort of phase. I’ve always been artistic. I did every school show at school, I did A-level drama. But what happened was: I was applying to medical school and I didn’t get interviews. All my teachers said, “Your application is very strong, we don’t know what happened.” It was very difficult at the time. I had played by the rules. I’d done what the books told me to do. But I think what that did is it really started to push my artistic side to the fore.

A teacher at my school said to me in the corridor, “I’ve heard about your medical school application. I’m really sorry. I think it’s a sign though.” And then he just walked off. It was in that moment that I was like, “Right. I’m going to be a singer. I’m going to apply for biomedical science, and while I’m doing that degree, I’m going to learn about the music industry.” And I sort of went on this quest to figure out: Writing songs and singing and open mics and youth arts clubs and free classes and all that kind of stuff.

I’d sing anything: Soul, R&B, jazz. People like Lauryn Hill, for example, were always on repeat. Whitney Houston as well. Those kind of amazing black female vocalists. And Pink! Her first album, Can’t Take Me Home—I still belt that out, even now, with real passion and guts [laughter]. But it was all just part of having a good time, having some curiosity. Music never featured in my mind as a career choice until what I believed was going to be my career choice, what offered stability became unstable.

…and the path from singing to acting

While I was doing my biomedical science degree, I started to go to this arts college in North London. It was the most extraordinary place. The founder, Celia Greenwood, ran classes all through the week for different age groups, different cohorts, for children with special needs and disabilities. Anyone is welcome, of course, but it tries to plug the access gap to the arts—to make sure that the arts are a right and not a privilege. Evening and Sunday classes was my course. And they were £2 a class which is just unheard of.

That’s where I met [the playwright and acting coach] Che Walker. Che is a working-class guy who grew up in Camden. He also studied under Celia Greenwood. The communities that you end up coming in contact with [at her centre], they tend to be Black or Asian, or less affluent if they’re White, or disabled. I mean, I could go through all the protected characteristics. Those that get pushed to the fringes. So even though Che is a white man, he has that diversity in his own experience. He taught Michaela Cole, Arinze Kene, Daniel Kaluuya. He’s taught everyone.

I went in there wanting to be a singer and had an amazing time in the singing class, but I also joined the drama class because why not? Two extra pounds, a few more hours on a Sunday.” And, one day, Che gave me a Shakespeare sonnet and said, “Write a song to that.” I thought, “Okay. Fine.” My love is as a fever. That was the first one. “My love is as a fever, longing still / for that which longer nurseth the disease.” Then he asked me to help him with [his play] The Lightning Child. Just with workshops at first. As serendipity would have it, they started rehearsals three weeks after my last exam at King’s. And he said, “Do you want to be in it?”

On finding—and offering—inspiration

I was so excited when I first saw Lupita Nyongo’s surname. She’s not Acholi—she’s from Kenya—but she’s from the wider Luo tribe. So I saw that surname on a trailer and I was like, “I know this name!” I clarified immediately with my mum. A similar thing with Obama. There’s the broader sense of seeing a black person generally. And then there’s seeing an East African person. And then there’s see a Luo person, a Ugandan person.

When Get Out happened—I watched it in America, actually—it was one of the most extraordinary films and performances I had ever seen. Obviously, I was a huge Daniel Kaluuya fan; we have mutual friends. But also he’s Ugandan, so my mum has claimed him completely and entirely. She’s always giving me updates about him and I’m like, “I know, Mum. It’s my job.”

Often, Ugandans refer to each other by their surname more than their first name. So [the author] Musa Okwonga, for example, I’d call him “Okwonga”. The first names tend to be Christian, because we were colonized; Christianity has become by far the biggest religion in Uganda. I’ve never really thought about it, but there must be some kind of interesting psychology there in Northern Ugandans’ choosing to opt for the surname to refer to each other more than the Christian name. Maybe it’s a kind of subconscious rebellion?

A couple of years ago, before the pandemic, I was in Oxford Circus, shopping. A man stopped me and said, “You’re that actress? Atim?” I said, “Yeah.” And he said, “We’re from the same place. I’m from Northern Uganda.” He’d just had a conversation with his daughter, who was studying history. She was preparing for her A levels and didn’t know what to choose. She liked history, but also loved acting. Her father told her that he’d seen a girl in the newspaper. “She’s from our part of the world,” he said. “She does acting and academia as well, so you can do it too.”

I talk a lot about the honours, the MBE. I read the invite and it said, “We want to give you this for services to drama.” And I was like, “I gave my services to drama, and continue to do so. And I pay my taxes weekly. So yeah, man, give me that thing!” [laughter] But also: Write me in your books, so that when the time comes to look back and say who was here and who was doing what, my name is there. My name is absolutely there, along with the other MB, OB, CB, Dames and Sirs. Beyond the optics, I want to be able to create opportunity, I want to be able to facilitate, to find people and recognise their talent when they might otherwise be overlooked.

On the allure of long hair

My hair was either braided or relaxed until I was 16. But I’d always loved natural hair. I remember saying to my mum, “I really want an afro.” She said, “You’re going to have to cut off your relaxed hair and start again.” And I was like, “No. I don’t fancy that.” [laughs] It absolutely wasn’t anything to do with the texture. It was just to do with the length. Length signified a sort of femininity and a beauty: All the girls have long hair and the boys have short hair. So me being somewhere in between, what does that make me?

Embracing my feminine side was quite difficult. Being a dark-skinned black woman, being tall, always tall for my age, very slim, lanky. Always getting stared at. Always just sort of not fitting in. I was a massive tomboy at school. I still am really. I’m in touch with my masculine and I’m happy with that, but there needed to be some balance. I think I de-feminised myself because society sort of did that to me as well. Being feminine didn’t make sense for somebody like me, who didn’t have the long flowing hair, who was darker skinned. All of that takes you out of the running, in a more romantic sense.

When I was 16, I started looking through all these magazines and saw these kind of cool choppy styles. They were mainly magazines catering to white hair but I was like, “This is amazing.” So I went and I got my hair cut with my best friend, DJ Juba. Pamela and I—everyone calls her Chinwe now, but I still call her Pam—were the two black girls in the school. We’re so different, but I think we sort of complement each other in that sense. She had just got her Afro cut and, for both of us, it was an act of rebellion. We were the only black girls in that part of Essex…but Romford tended to be where we all converged, and a lot of girls had weaves with centre partings. Nothing against that at all—but there was a derision that we faced for wearing our hair short. I was inspired by Kelis in her Lil Star video. She’s got her head shaved on the side and then it’s all kind of curled over to the side. I wasn’t allowed to do peroxide blonde hair at school, but I shaved the side. There was this realisation, then, which sounds really simple: “Oh, my hair can grow back. I’ll do something to it and then it’ll grow back.” The aspiration to keep hold of length, I think, is something a lot of black women still really focus on. And fair enough, if you want long hair then, again, no judgement. But I sometimes wonder what’s behind that aspiration, to be able to retain length, whatever that means.

I was always under the impression, when I was younger, that my hair didn’t really grow. But now I cut my hair and it grows really quickly. It’s probably growing at the same rate, but I’m aware of the growth now that I’m less precious and less focused on it. Just more in tune with my hair and what it needs, and how it works, and having fun with it.

“I understood that although I had a similar experience growing up as a lot of my White working-class friends did, they have a generational lineage here that I don’t have. And so, if I fail, if my mom fails, that’s it.”

On working—and not working—as a model

Just after I’d cut my hair, and shaved it, I was scouted at The Underage Festival. [Modeling] was another sort of creative experience for me. But I didn’t actually work that much. [laughs] I was sort of stuck in this “editorial, but not quite” space. My hair wasn’t natural at the time; it was short but relaxed. I think people were confused: They either wanted me to be like an Alex Wek, who was occupying that East African, tall, dark skinned, short haired space. Or like a long-haired Oluchi. And I’m somewhere in between. When I was at London Fashion Week in 2020, I was talking to Edward Enninful of Vogue, and he was like, “It’s so funny, because now all the girls on the runway look like you.” But I was lucky. Because I was occupying this no man’s land, I got all the weird interesting stuff. It took the competitiveness out of it for me, because that wasn’t the focus. I was able to just enjoy myself.

On having a good time

I was always an ambitious child. I loved science. I loved the arts. I loved school. I genuinely loved those things. Still, it’s important to keep an eye on how much of that is passion versus

pressure, an understanding that “I have to succeed because that’s what we came here for.” I don’t think I was consciously aware of that as a kid, but subconsciously I understood: I don’t have roots here. Lots of my white working-class friends, for example: We had a similar experience growing up, but they have a generational lineage here that I don’t have. And so if I fail, if my mom fails, that’s it.

As my career starts to progress in the direction that I want it to, I find myself wondering what new challenges are going to awaken. Even when I’m working in the theatre—which is, in terms of production size, smaller scale—I really just want to have a good time. Because of the way I got into this job, I’ve always tried to be very uncompromising about having a good time. Because why else am I here? I had a few paths that I could’ve chosen to go down, right? I could have tried to continue to become a doctor, or done something else with my biomedical science degree. I could have been a singer or I could have gone elsewhere. But this is the thing that presented itself to me and I’ve really pursued it. I don’t see any excuse for having negative experiences that can be avoided. I’m not saying that everything is going to be perfect, but I always try to set my bar and stick to that: I’m here to have a good time.

On that issue

(Casting Black British vs African American actors)

I’ve been watching this debate kind of quietly, because I’ve been very keen to make sure that I’m listening, right? It can feel very personal—a sort of personal attack—so I’ve wanted to really listen. And what I think is happening is a culture clash. I’ve got lots of African-American actor friends, and we’ve spoken about this. One thing that has come up is that they don’t know a lot about black people in the UK, unless they’ve stayed here for a little while—and a lot of them haven’t, right? My instinct is that we as black British people have a proximity to other parts of the diaspora and the continent that maybe is not the same in the US. One of my friends, Abigail, who worked on Underground Railroad with me, she was like, “I’ve kept my mouth shut because I know that I don’t know a lot about Black British history. I’m not going to jump in with my assumptions.” I think many people in the US simply aren’t aware, and I think that’s down to the education that they receive. It’s the same here. I wasn’t taught about colonialism at school. I didn’t know what colonialism was until I was an adult.

In the UK, I see myself as a black actor who serves the stories of black people around the world. I approach every part that I do—even the parts that are closer to me, whether they’re British or working class or Ugandan—with respect, making sure that the part has dignity, that I’m doing the work to do the part justice. That’s not to say that I believe I have an assumed right to every single part written for a black woman. Obviously not. I don’t have a problem with somebody saying, “For this project, I want everyone to be from Nigeria.” If the creative team have decided that that’s going to enrich the project: Great. But on the flip side, I don’t think there’s anything wrong with not making that specification, with deciding to cast the net a bit wider.

I have seen lots of African-American actors not play Americans. And I’ve always celebrated those performances. I’ve seen them as black actors who are serving stories across the diaspora, across the continent, across the global community. My ambition for the industry is that all of us can play each other. I’d love more Brits to play more Americans. I’d love more African-Americans to play more Brits. The black community, globally, has experienced so much segregation in its history; just look at the continent of Africa, at those straight lines, the borders. Then socially: The colourism, all the other hierarchies that have been woven into our communities. I’ve actually taken the personal aspect out of it, and worry in a wider sense because I don’t want us to fall back down that path.

The only way we can advance as a global community is through a kind of coming together— through collaboration and celebration. You see it happening in music: Afro-beats, hip-hop, UK drill. I want us as actors to do it as well. That’s definitely the focus of some of the stuff I’m trying to do, because this unification could be something really special.

On the importance of being fervent

I don’t think it’s arrogant to say that I work incredibly hard. One thing I will always do is give you 100%. I will always, always endeavour to do that. So there’s a lot of unseen work that happens, as I’m sure is the case for lots of people who are very successful. It’s not just the final product—it’s the graft and the dedication. People say, “Luck is preparation and timing.” But also: I’ve said yes to lots of things. I’ve grabbed hold of lots of opportunities that maybe other people might have shied away from.

I see every moment as an opportunity. I was in a singing class when I met Ché Walker; I wasn’t in the drama class yet, right? But in the singing class, we were doing a project for which we teamed up with the drama class and, because I could also play the piano, I was helping everyone learn the music. No one asked me to, but I was accompanying people on the piano and Ché saw that. When I joined the drama class, he already knew me as musical. I remember that we all had to do Shakespeare monologues. I can’t remember which one I had; maybe it was Agamemnon? But I came in and I had learned it. Other people in the class hadn’t. Again, Che saw that. So he asked, “Do you want to write the song to this sonnet?” “Do you want to come and help me with a workshop?” I had proved myself. I didn’t realise that that’s what I was doing at the time—but I proved myself.

On falling in love

Do you know what? I’m falling in love with myself. There you go. I’ll say that. I’m finding out how to fall in love with myself.