Truth is as Strange as “American Fiction”

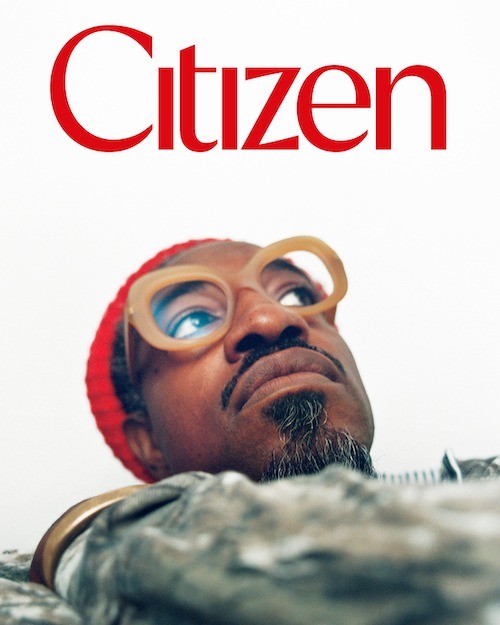

Introduction Text by Nora Taylor

Photography by Jelani Cobb

Issue 003

“It’s exhausting, man.”

American Fiction arrived on the film festival season with a bang. By the fall of 2023, the buzz had built to a palpable roar as reviews, interviews, and awards came rolling in. Based on the novel Erasure, by Percival Everett, the movie stars Jeffrey Wright, Issa Rae, and Tracee Ellis Ross. But for most of that time, the film’s director and writer, Cord Jefferson (CJ), was a one-man PR machine. Due to the SAG strike, he alone fielded Q&As, sat on panels, and spoke with the press.

Novelist and writer Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah (NAB) caught up with Jefferson a few days after the strike ended to talk about his journey from journalist to in-demand TV writer to even more in-demand movie director. The pair had met briefly the night before during a screening of American Fiction, one of the many stops for Jefferson on the movie’s fast and furious promotional train. The next day, on Zoom, Jefferson appeared as a 7-digit phone number across a black screen, dialing in from a cellphone while he was in transit to New York’s John F. Kennedy airport. Though in between one city and the next, with Nana, Jefferson was present, tempered, and familiar as they discussed the perils of satire, telling Black stories in a white-dominated industry and the thrill of bringing the story of American Fiction to life.

“It’s a very gatekeeper industry, and they don’t want to let people in. And so I just try to tell people all the time, try it. You can do this.”

NAB: Let’s get into it. How are you feeling getting the news that the strike has ended?

CJ: I mean, so excited. I wanted the strike to end for any number of reasons. A lot of people can get back to work. But my most selfish reason was that these actors in the film are getting a lot of really incredible accolades, and I want them to be out in front accepting those accolades. I’m very happy for them, particularly Jefferey Wright. And I think that they deserve it. I’m happy that they’re able to come out and talk about the movie and celebrate it and be celebrated for their work.

NAB: Right, absolutely. And, it’s a little less pressure? You don’t have to put the team on your back promo-wise as well.

CJ: It’s exhausting, man. I love the movie, and I’m very proud of it, so I’m happy to talk about it as much as possible, but it’s just tiring.

NAB: So, as this is your first theatrical release as a director, and I know it’s kind of hard to reflect on things as they’re going, I was wondering if you could talk just about that first time you got to sit in a full theater and watch the film and just experience it with people. What was that like?

CJ: Incredible man. I mean, terrifying, if I’m being honest. It was very, very scary. But also, when you realize that the movie’s working, when I realize that people are laughing where I want them to laugh and gasping where I want them to gasp, that is when you start to see that the material is connecting with people. It’s incredible.

For so long, I’ve just been a writer, and you can’t really watch people experience your work in real-time. You can just make your work and put it out there, and that’s satisfying. It is nice to do that, and I sometimes miss that kind of writing, but there’s something different. There’s something satisfying in a different way about seeing people respond to the material in real time and go on this journey together. And to be among that, I mean, it feels like flying.

NAB: Yeah, and it felt special. It just felt really good to be around the people and to genuinely laugh at things. Now that you’ve watched the last cut of your film probably an insane amount of times, I’m wondering what parts of you that might have existed in your journalism or your work in other mediums do you find maybe popping up in the film? Do you see any of the things that you are interested in or stylistic things that might have found a new life or a new interpretation in this new medium for you?

“About three years ago, I had a note come down from an executive that I needed to make a character blacker.”

CJ: Man, that’s an interesting question. I don’t know that I’ve carried over anything necessarily into the film. I mean, I will say that I think that journalism really helps me when I make films and that it guides my decision to work on specific things. One of the things that journalism has really helped me do when it comes to film and television is think about the “why now?” of it all. Journalism helped me understand it’s the question you ask yourself every day – why should I write? Why should this story go on the front page? Why should I be writing this article instead of the million other articles I could write? What is the urgency behind this? And so I think that that is really something that I now ask myself before I sit down to write anything now in film and TV.

It helps you find your voice.

And I think that asking yourself why this deserves to be seen, people find themselves distracted a lot these days. There are a lot of things that they could be doing with their time besides watching your movie or TV show. So I think that you need to find as many reasons as possible to get them to watch something. And I think that sort of relevance and timeliness is something I learned in journalism.

I was working in TV for about six years before I started writing this movie. The thing that I took from TV to film is that one of the things that makes TV nice to create and watch is the prolonged time you spend with characters. If you’re watching something over the course of several seasons, you really start to understand the characters on a very deep personal level. And so, to me, that commitment to character sometimes gets tossed by the wayside for films because you have a plot, and you’ve got to get through the story in 90 minutes. But that’s something I tried to bring over, just a commitment to character. And I really wanted to make sure that the actors got good material to work with and felt like they were sort of playing real, lived-in human beings. And I think that’s one of the reasons why I was able to get such a tremendous cast was that they felt like they were getting real parts. They felt like they were playing real people and not just set dressing in order to move the plot forward for the white leads.

NAB: That’s really real. This is a legit all-star cast, and I think that term is used a lot, and oftentimes, it’s used meaning a lot of famous people, but in sports, all-stars are the best players. And in this case, it still applies. What was it like managing such a cast? Especially as a first-time director, and are you super spoiled now because this is a crazy high bar to start with?

CJ: I think I started reading the novel in Jeffrey Wright’s voice. I started picturing him when I was reading the book the first time around, so he was the first and really only person I went to with the script. If he had said no, I have no idea what I would’ve done; that would’ve been a disaster. Once we got him though, I was confident our luck had run out. I was like, well, we got Jeffrey, we’re not going to get anybody else of that caliber, so we’re going to have to probably get our fifth, sixth, seventh, eighth pick. But then we sent it to Tracee, and Tracee signed on. We sent it to Sterling [K. Brown], and Sterling signed on, and we sent it to Issa Rae, and Issa signed on. And it just continued: Erika Alexander, John Ortiz, Adam Brody, and Leslie Uggums.

It was intimidating to manage that cast. It was frightening for me because these are people who have such deep resumes and come from such a great pedigree that I was worried that I was going to let them down as a first-time director. But the great thing that I learned is that the way that you become a great actor is by being collaborative, and so I was able to see that these actors were just all very collaborative, and nobody came in with an attitude.

They were all wildly prepared and had great ideas for the characters, great ideas for their costumes, and great ideas for things to add to scenes. I felt very protected by them, and I hope that they felt protected by me, and it did make the job easy. Making the movie was the hardest thing I’ve ever done, but it made it easier for sure.

NAB: Last night, you said something that felt really honest during the talk back about learning on the job and how you had a crew that was really open to that. I think for an aspiring filmmaker, that’s something really encouraging to hear. But if you had to talk to aspiring filmmakers about what it is to learn on the job and some of the best things that you learned, what would you say?

CJ: I tell every writer I talk to now that they should try directing. I realized that when I was writing a scene, I was already thinking about what the characters were wearing and what the room would look like that they’re in. I was already thinking about how I wanted them to move around the space. You’re thinking about how you want this joke to land when they tell it. And so I realized, once I started working on the film, that I was already making these decisions in my head. I just wasn’t articulating them to anybody because it wasn’t my job. Something to realize is that I think that people feel intimidated by directing. I think that I certainly did.

I was working on Master of None season two, and Aziz Ansari asked me if I’d ever thought about directing. I was like, “It’d be cool, but I didn’t go to film school.” I don’t know anything about cameras or anything. And he said, all you really need is just a vision, and then you need to be able to articulate that vision to the people around you who understand those technical things.

I think that oftentimes this industry likes to build up unnecessary obstacles in front of jobs. It’s a very gatekeeper industry, and they don’t want to let people in. And so I just try to tell people all the time, try it. You can do this.

Something that I would tell first-time directors is just to be honest. Be honest with people that you don’t know everything. Say, listen, I don’t fully know what I’m doing, but I can learn, and so I am going to need you to teach me. This is a collaborative art form. You need a hundred people a day to help you make this thing and over the course of it, hundreds of other people. And so just be open and kindhearted with the people that are around you, and everything’s going to go much better.

NAB: I imagine there must have been something that felt kind of meta about making this film or maybe even more so in getting the film to get sold – just having a movie that is about a black creative trying to survive in the ridiculousness that is the market and the institutions, which almost inherently forced you to intersect with whiteness. I wondered if in writing or shooting this film, there was sort of a cathartic energy. Were there any sort of intersections with industry slash whiteness that made the film again feel like it was playing out itself?

CJ: There’s a ton of my experience in the movie. It did feel cathartic making it because these are issues that I’ve dealt with first in my journalism career and then in my film and television career. About three years ago, I had a note come down from an executive that I needed to make a character blacker. They told me that note through my manager, and I told my manager that if they really wanted to have this conversation, they needed to get on the phone with me and tell me what blacker means. And guess what? They dropped that note because there’s no way in the world that they were ever going to have that phone call with me because they knew they’d sound stupid.

There is a lot of nonsense that you still have to deal with in this industry. And I think that a lot of my fellow Black writers have dealt with it. I think that, but it’s also not just a Black problem. I think that there are just a lot of people who feel that the industry has very rigid restrictions when it comes to the stories that it will allow people to tell about themselves and the industry will tell about these groups of people.

It’s been interesting to see people, on the other hand, come to the film. I had a white woman come up to me after a screening, and she said, ‘That was a very uncomfortable screening for me. I laughed a lot, but it was painful laughter because I recognize myself in some of these things.” I was happy for her and proud of her. I think that when I’m experiencing a piece of art, and it’s making me uncomfortable, that to me feels good because I think that it’s challenging me, and I like to be challenged. And so for her to come over and admit that she was leaning into the discomfort and sort of experiencing it and thinking about it, that, to me, is how people change. That’s how people learn to change, and that’s how people learn to grow.

“To me, when satire becomes farce, it allows the audience off the hook to just think of what they’re watching as some silly comedy.”

NAB: You mentioned how you’re playing with satire, but you didn’t want to fall too far into farce.

CJ: I believe that occasionally when you let the satire become farce and become silly, I think that people stop thinking about the underlying themes of what you’re doing. For me, I just wanted to make sure that we had satire, but that the film felt grounded and real because I didn’t want people to walk away going, “Oh, that was silly, wasn’t it?” I wanted people leaving the theater laughing with a smile on their faces but with something to think about when they leave. To me, when satire becomes farce, it allows the audience off the hook to just think of what they’re watching as some silly comedy.

NAB: I think it’s a really hard balance to hit, and I talk about a lot of my own work, and I think you did it tremendously. You hit this at the park. I’m really excited for it to be out to the world.

CJ: I appreciate it, man. I appreciate it.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.